The 1918 Influenza Outbreak

Monday, April 6th, 2020 in history of Travis County, news, research. No Comments

During the fall of 1918 and the winter of 1919, an epidemic of influenza affected much of the civilized world. An estimated twenty-five million Americans experienced what became known as the Spanish flu; an estimated 550,000 died from the disease. More U.S. soldiers died from the 1918 flu than were killed in battle during the war. In just one year, the average life expectancy in America plummeted by a dozen years.

When the 1918 flu hit, doctors and scientists were unsure what caused it or how to treat it. There were no effective vaccines or antivirals, and World War I had left parts of America with a shortage of physicians and other health workers. Of the available medical personnel in the U.S., many came down with the flu themselves.

Prior to 1914, few people traversed long distances, limiting the spread of infectious diseases from one place to another. The war saw the mobilization and movement of large numbers of troops and related personnel, both within and between continents; it also uprooted the lives of millions of non-combatants, especially in Europe. People from places far apart became more directly connected – and more liable to be exposed to any new form of the flu.

Army recruits in World War I were brought together to live in close proximity in army camps, barracks, ships and trench dugouts. Soldiers with mild strains of the flu virus were left in the trenches, and those with severe illness were sent home. As they made the trip back home, they infected those who came in contact with them, due to the highly contagious nature of the disease.

In Austin, the disease spread quickly. Early reports assured the public that though the disease was highly contagious, there was no just cause for alarm. However, this quickly proved to be false. On September 27, 1918, there was one reported case of influenza at Camp Mabry. On October 4, 900 cases of influenza were reported there.

As the number of cases grew, more medical facilities became involved. Hospitals became so overloaded with flu patients that schools, private homes and other buildings were be converted into makeshift hospitals, some of which were staffed by medical students. At Seton Infirmary on West 26th Street, the Army set up large tents on the grounds and converted a three-story fraternity house into a temporary shelter for patients.

Edna Shultz, matron of the City Hospital (later known as Brackenridge Hospital), reported, “The city officials came to me and said, “Put your white dress on and take charge.’ …The city officials told me to get everybody out of the hospital who wasn’t seriously ill and prepare for the worst. Then they brought in Army cots and I was ready.”

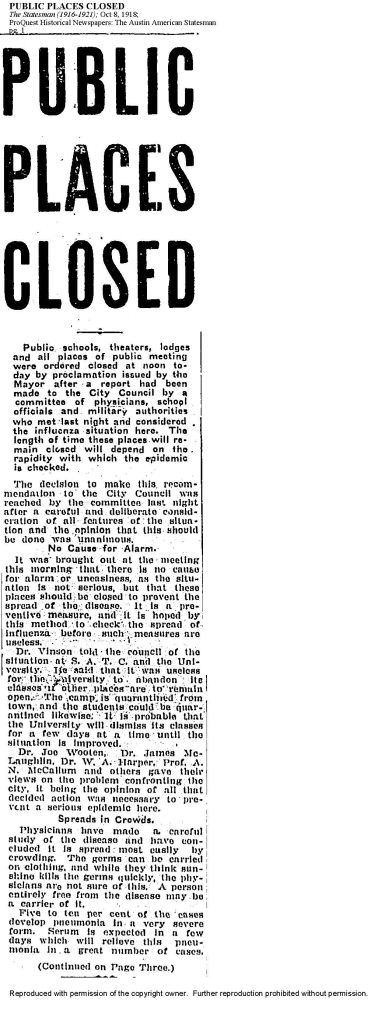

Quarantine was placed on Camp Mabry. The University of Texas first suspended classes for three days, but then announced that school would be dismissed until further notice. On October 8, 1918, the City Council adopted an ordinance that closed “the state university, all public and private schools and colleges of the City of Austin, all churches and lodges and all other places of assemblage where people gather for religious, social, fraternal, political, business, or other purposes for the period of thirty days from the date of the enactment of this ordinance.” On October 18, it was announced that Travis County schools would remain closed indefinitely.

By the end of October, area health officials were reporting that the influenza epidemic was under control in portions of Texas and that the situation was gradually improving. On November 2, the Austin City Council repealed the ordinance banning all public gatherings, and schools were reopened soon after. Camp Mabry prepared to lift its quarantine, and temporary hospitals that had been opened throughout the city began to be closed.

While no official record was kept, newspaper estimates put the Austin and Travis County mortality rate at approximately 277, with thousands infected.

Worldwide, the flu pandemic came to an end by the summer of 1919, as those that were infected either died or developed immunity. The exact numbers are impossible to know due to a lack of medical record-keeping in many places. However, some estimate that The Spanish flu infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide—about one-third of the planet’s population.