The Haunting of the Old Travis County Jail

If Hubert Harvey hadn’t fatally stabbed that young Austin man on Halloween night in 1916, he might have lived to see the fine new Texas

Highway Department building go up where the Travis County Jail once stood.

But that’s not how it worked out. At 1:50 p.m. on Aug. 23, 1918 Sheriff George Matthews sprang the trap on the gallows inside the jail and Harvey paid for his crime at the end of a rope.

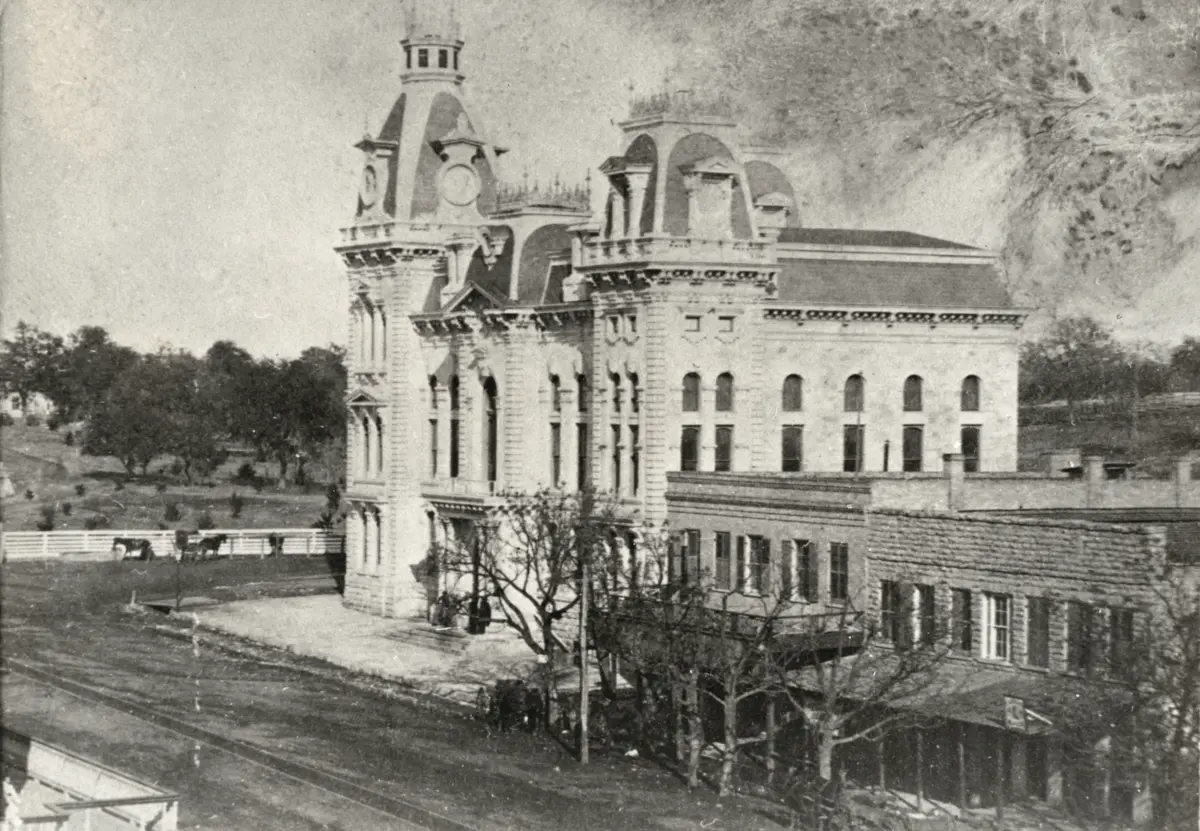

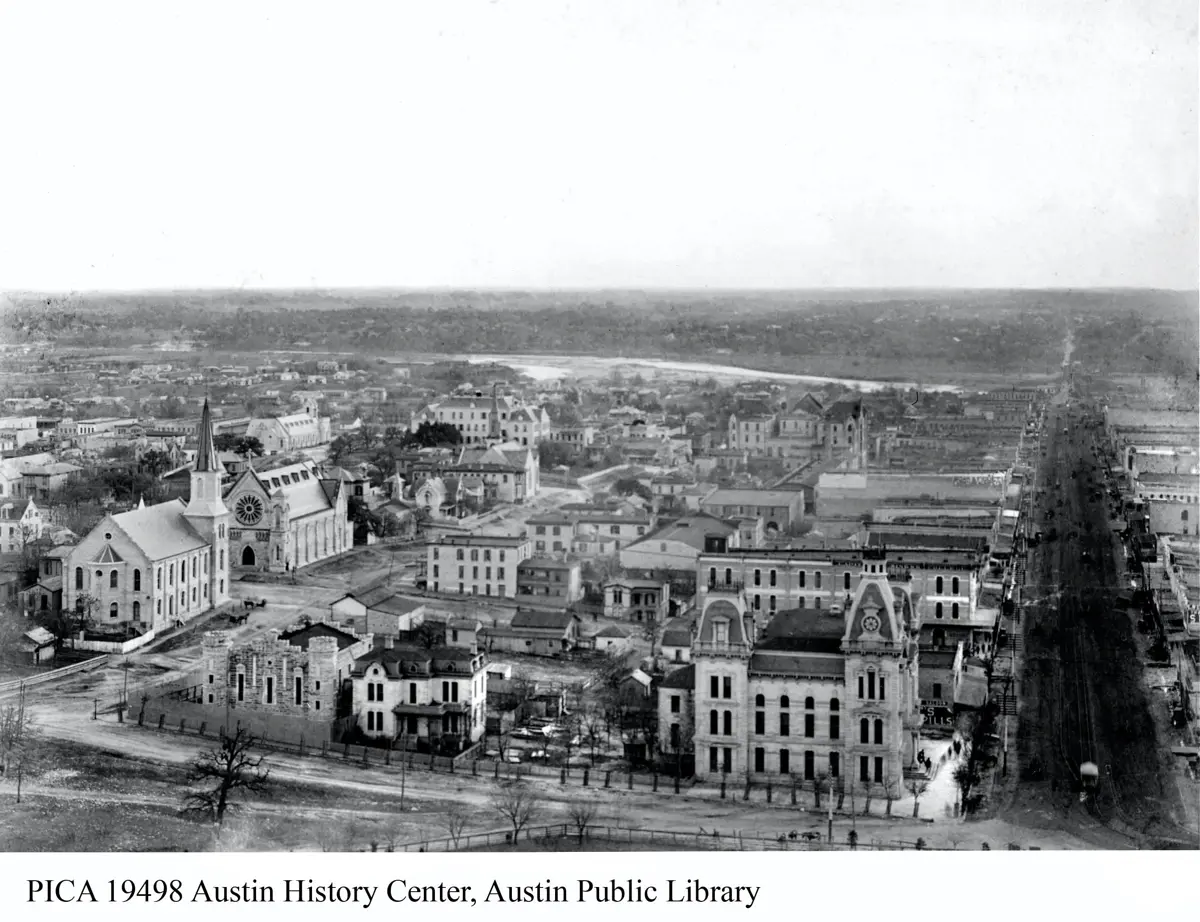

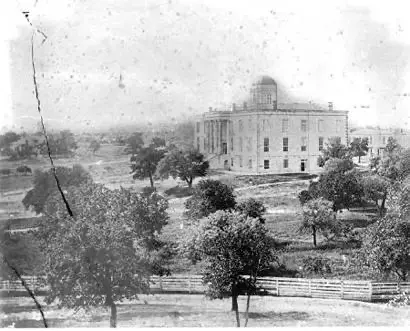

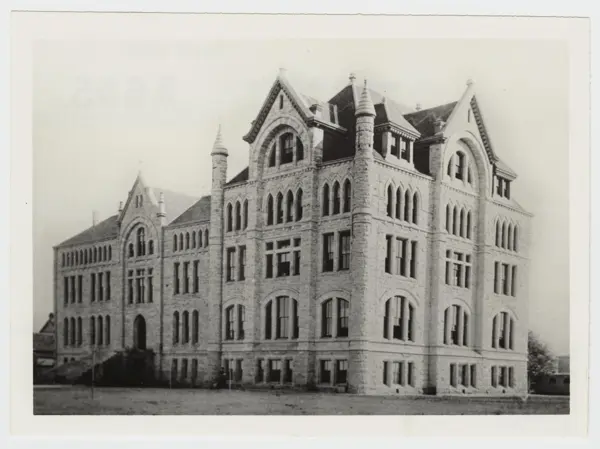

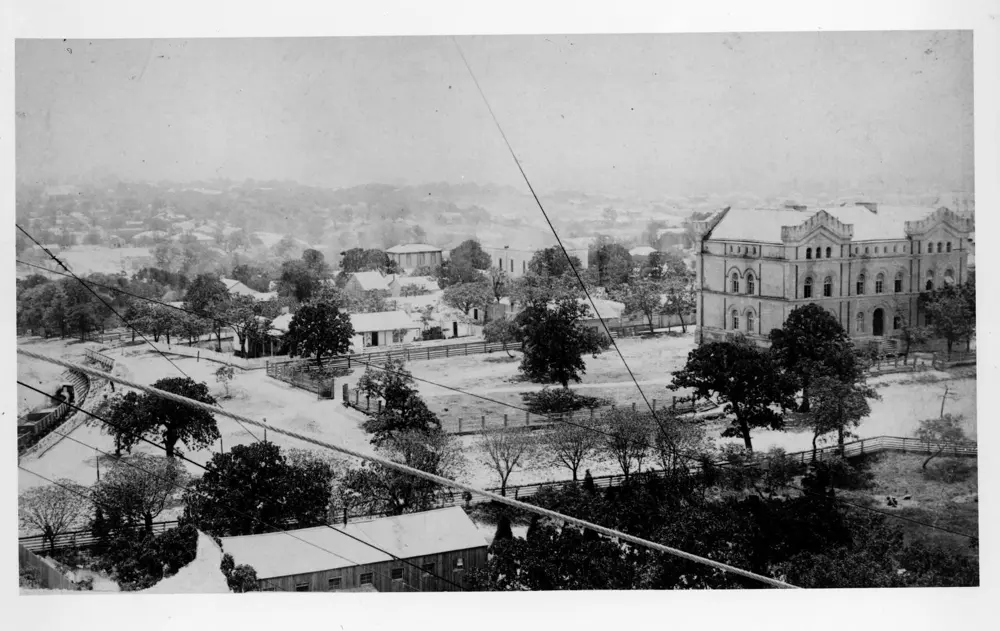

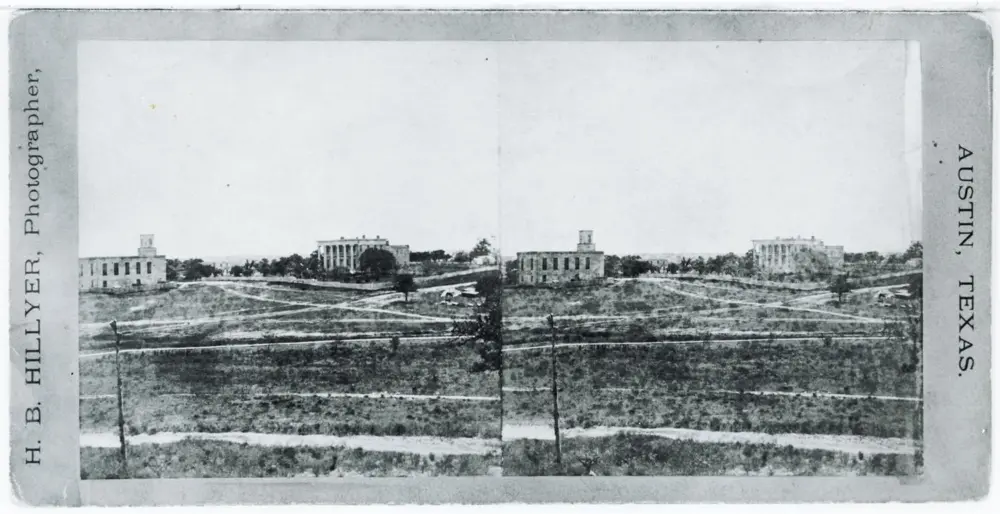

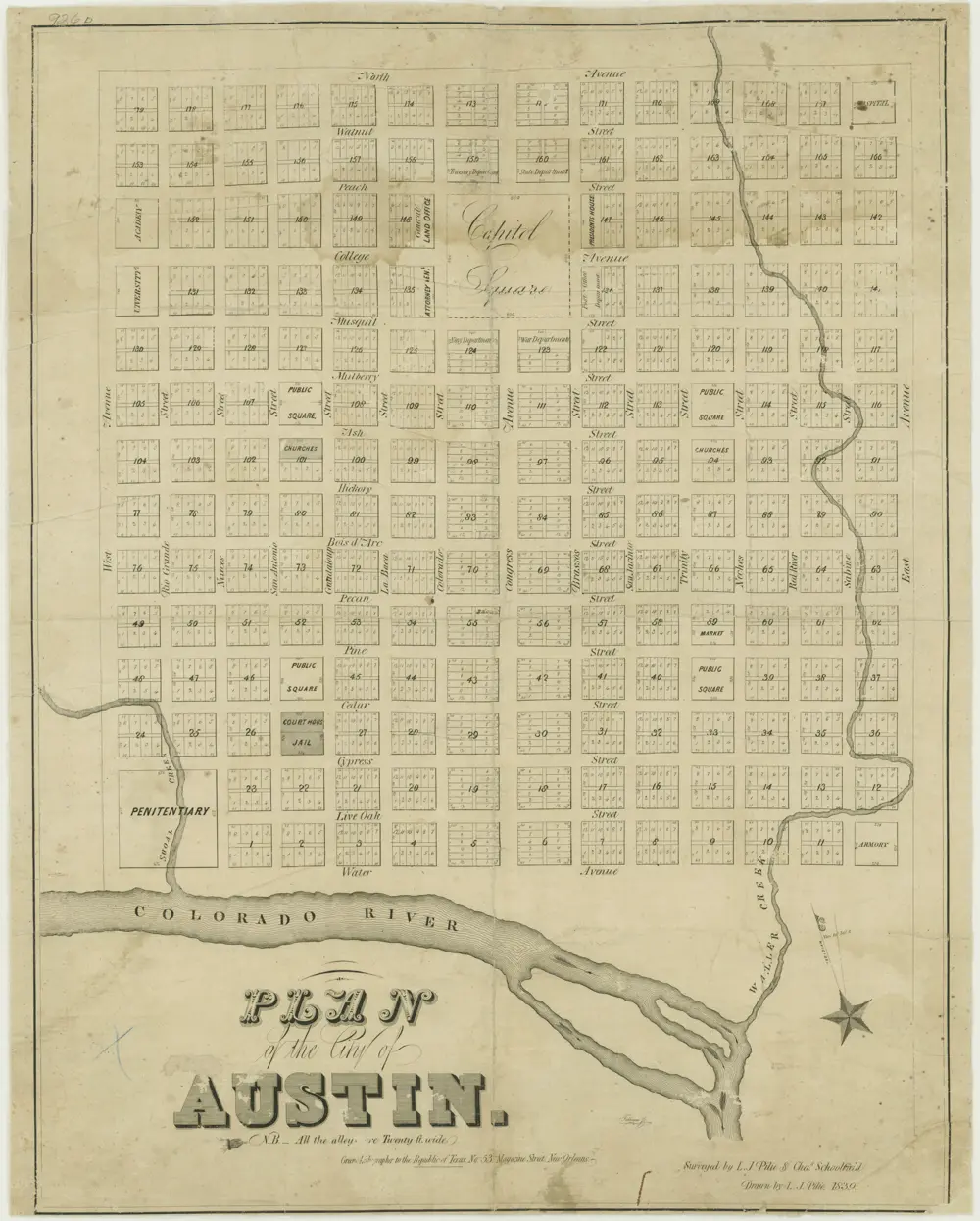

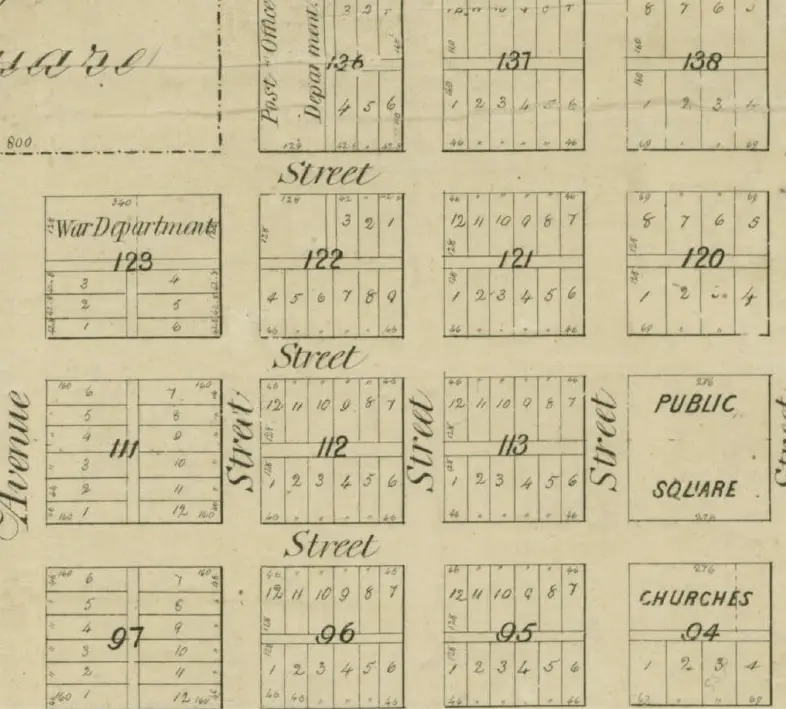

Harvey, 34, had the distinction of being the last of nine men legally hanged in the castle-like stone jail, built for $100,000 in 1876 at the

corner of 11th and Brazos streets — present location of the Dewitt C. Greer Building, headquarters of what is now the Texas Department of Transportation.

Who knows? Maybe Harvey’s spirit has something to do with the mysterious footsteps and strange noises some TxDOT employees have reported hearing at night when the building’s supposedly empty. But for anyone who believes in ghosts, there are plenty of suspects.

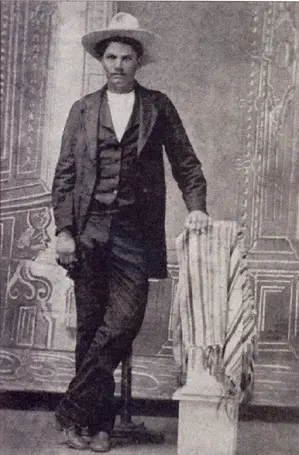

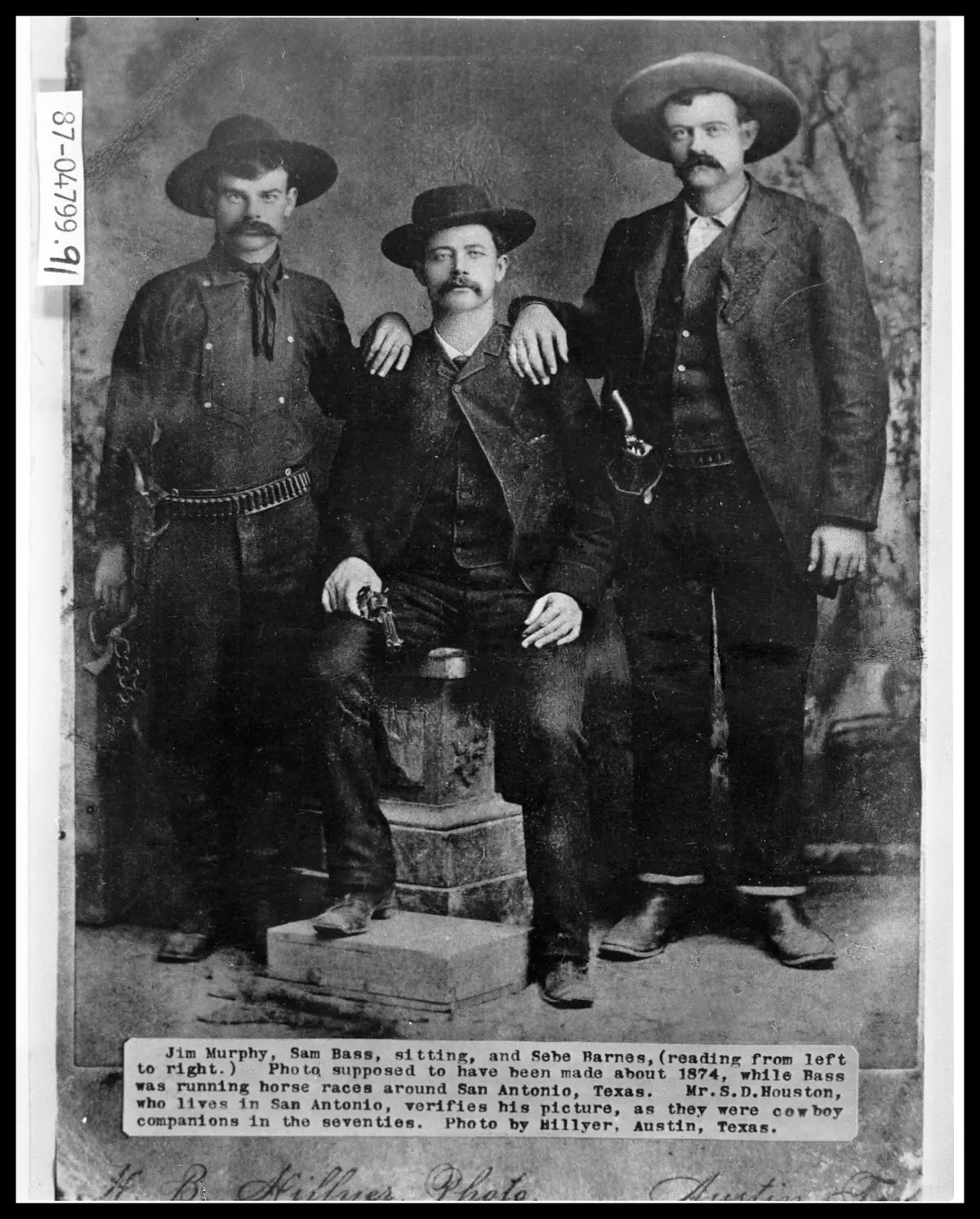

John Wesley Hardin, Texas’ deadliest 19th century outlaw, cooled his heels in the still-new jail until his transfer to the state prison in Huntsville. John Ringo, another famous outlaw, did some time in the Travis County slammer before moving west to Arizona.

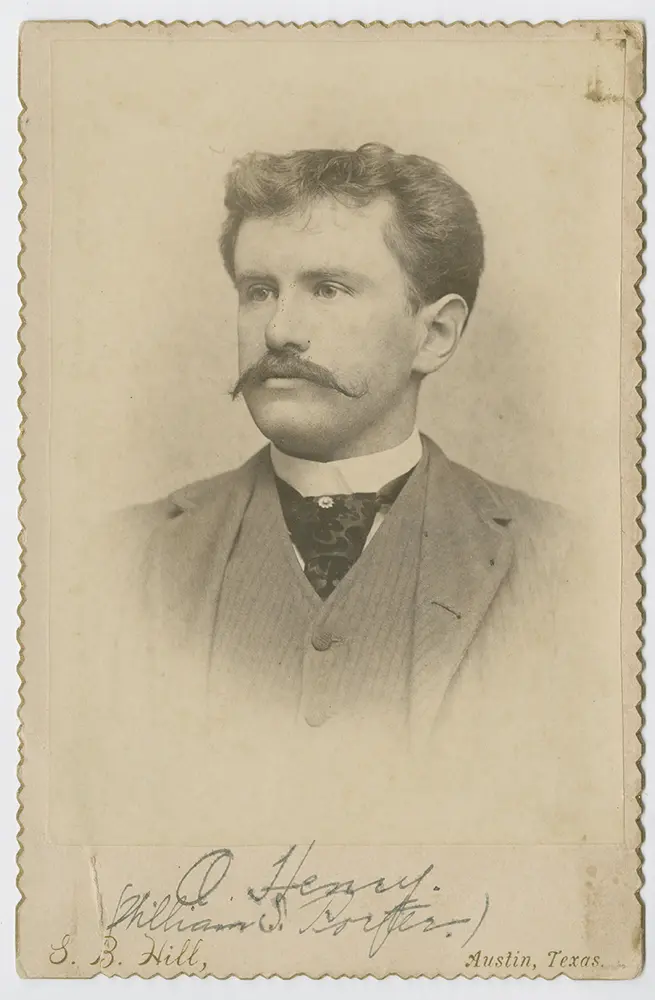

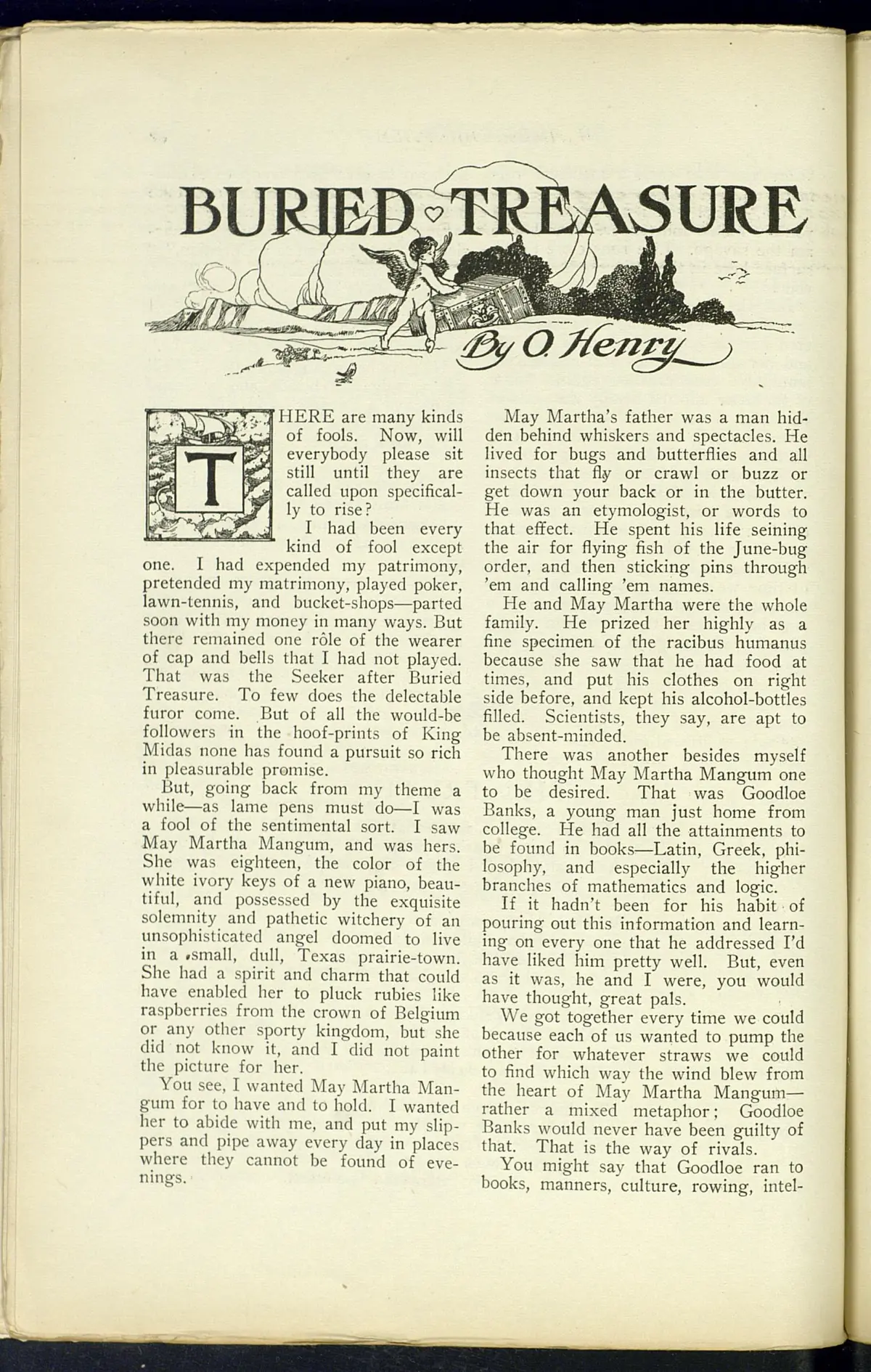

A more genteel inmate was William Sydney Porter, a popular young man with a penchant for puns, pilsner and games of chance. Later known world-wide as O. Henry, the short story writer got to reflect on the literary life for a while after being booked on a federal bank embezzlement rap in 1898.

The Highway Department, crammed in a state office building across the street from the old jail, saw the impending move as an opportunity to get

land for a new headquarters. Negotiations soon began with Travis County to buy the property.

“We wish to renew our recommendation that the State Highway Commission be permitted to erect a building to house the State Highway

Department in Austin,” read the fifth of nine recommendations made in the department’s seventh biennial report. “Such a building,” the 1930

report continued, should include “a laboratory, research department, and ample other space for carrying on its activities, now and in the future.”

Despite the transportation agency’s interest in the jail property, some Austinites suggested the old jail should be remodeled and transformed into a

public library named in honor of O. Henry.

In the end, practicality trumped preservation and the state razed the old jail. The department used free labor to clear the site, ordering a class of

Highway Patrol cadets then in training at CampMabry to do the job.

At a cost of $455,151.74, the new building opened in the summer of 1933 — only three years after it was requested. Impressive as the new

Highway Building was, nearly another 20 years went by before the agency got around to installing air conditioning. That cost $170,642 in 1951.

The building has seen various renovations since then, but no ghost busting.

Until 1923, under state law the sheriff of the county in which the condemned

person had been convicted bore the responsibility of carrying out an execution.

After that time, executions were by electrocution at the state prison in Huntsville.

For the superstitious, these are the other potential Greer Building “haunts”:

• Taylor Ake, 18, hanged for rape, Aug. 22, 1879

• Ed Nichols, 21, hanged for rape, Jan. 12, 1894

• William Eugene Burt, hanged May 27, 1898 for killing his wife and two children.

Police found their bodies in a cistern at 207 E. 9th St.

• Sam Watrus, 30, hanged Jan. 27, 1899 for murder, rape and robbery

• Jim Davidson, 30, hanged Nov. 24, 1899 for murder, rape and robbery

• Henry Williams, 30, hanged May 2, 1904 for murder and rape

• John Henry, hanged July 12, 1912 for murder

• Henry Brook, hanged May 30, 1913 for murder

While none of these men ever had to worry about the infirmities associated with the passage of time, by the late 1920s, the jail had begun to show its age. And so had the adjacent county courthouse at 11th and Congress. When Travis County officials decided to construct a new courthouse at 11th and Guadalupe in 1930, the plans included a larger, state-of-the-art jail on the top floor of the new building.

Text courtesy of Mike Cox, “Texas Tales” October 14, 2010, http://www.texasescapes.com/MikeCoxTexasTales/Haunting-of-Old-Travis-County-Jail.htm