Chapter 1: Vice

Even after Texas was admitted to the Union in the mid-19th century, the state held fast to an ideal of freedom which created a climate for the development of vice. In fairness, the U.S. as a whole during the 19th century was much more tolerant of vices like gambling, alcohol, and drugs than it is today, but the environment in many parts of Texas was even more tolerant. In towns across Texas, including Austin, saloons, brothels and gambling halls appeared almost overnight. As towns grew and prospered, the primitive lantern-lit, dirt-floored structures were replaced by one-story wooden buildings with false fronts, and later by imposing brick buildings with ornate bars, huge back-bar mirrors and brilliant chandeliers.

Guy Town

Artifacts from a privy located behind the site of a tenement building on the City Hall block. From top to bottom, a decorative glass roller skate, a bone make-up brush, and a syringe. Photo courtesy Hicks & Co.

Between 1870 and 1913, there was an eight square block section of Austin referred to as “Guy Town.” Also known as the First Ward, this was Austin’s red-light district. The community was populated with saloons, gambling houses, dance halls, and brothels. The Austin City Council first banned prostitution in June 1870. It was also illegal to keep a “bawdy” or “disorderly” house – that is, to operate a brothel. Despite this, prostitution was alive and well in Austin, buoyed by the steady influx of troublemakers and politicians alike. Some brothels were high-class, and some less so. They were connected to saloons or pool halls or even grocery stores through a back door, while others were cramped little apartments with doors opening into alleyways. The neighborhood was home to hundreds of prostitutes, slowly building momentum from the early 1870s over the next several decades.

Prostitution

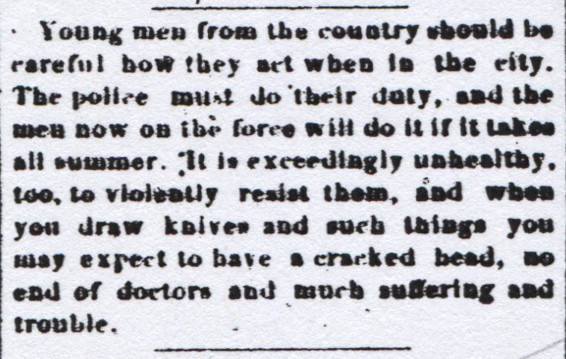

As time went on, Guy Town became Austin’s focal point for scandal, noise, loud music, fights, and disturbances. With an anti-prostitution measure firmly impressed in the city ordinances, Austin was legally equipped to handle any red-light problems it might encounter. However, the police did not try particularly hard to enforce the law. While hassled often, prostitutes were only rarely arrested for plying their trade. Charges of assault, public intoxication, and use of abusive language were far more common, even when the arrestee was a known prostitute.

Gambling

Gambling was a popular form of recreation in early Travis County. As a new arrival to Austin wrote in an 1863 letter, “This is a great city… In the spring there was not a hundred souls here. Now there are 5 or 6 thousand composed of all classes – over one half being gamblers. You may judge something of the character of the people when I tell you that in 24 hours 4 men were shot in gambling houses and one man committed suicide. There is someone killed every day almost.” Unregulated gambling reached its peak in the 1870s, before communities began to establish more formal ordinances and enforce them more strictly. Despite these measures, gaming remained a relatively common pastime in Austin. Games included those such as poker, faro, craps, rondeau, euchre, pool, and monte. Austin had its fair share of professional gamblers who traveled the circuit from one town to another.

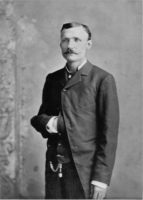

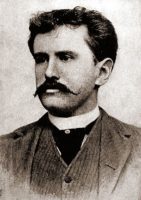

One such gambler was notorious gunman Ben Thompson, who also served as an Austin City Marshal. Ben Thompson was both a lawman and a gambler. Between 1874 and 1879 he made his living as a professional gambler, and he was elected Austin City Marshal in 1880 and 1881. Travis County Sheriff George Scott was himself charged with betting on pool in 1843, but his reputation apparently did not suffer too much as he was reelected for a second term soon thereafter.

Chapter 2: Crime and Punishment

Though 19th century Texas is associated with the gunslingers and outlaws of the wild west, most of the crimes committed in early Travis County were petty in nature. This chapter highlights some of the unusual offenses found in early Travis County court records. This chapter also covers the establishment of the first county jails and their use as a place of execution for those who had been sentenced to die.

Unusual Crimes

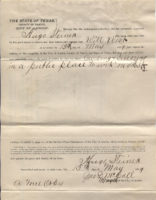

Early Travis County court records reveal a variety of miscellaneous offenses, many of which are unusual in today’s time. Travis County residents at one time could be charged with: indulging in exercise calculated to scare a horse, appearing in clothes not belonging to one's sex, rudely displaying a pistol, and playing City Marshal. Travis County Justice of the Peace, County and District court records from the 1800s include other charges such as enticing away a slave, failure to work public road, fast driving (on a horse), cursing and swearing in a public space, and betting on an election.

The First Travis County Jails

Although discussions began as early as 1840, the Travis County Commissioners Court did not contract for the construction of the first county jail until 1847. Local Mormons were hired to build the jail at a cost of $1,800. The structure was a small double log construction built on the “Court House Square,” at what is now 4th and Guadalupe Streets. This first jail reportedly was destroyed by fire in 1855.

That same year, Travis County authorized a contract for the construction of a new county jail, along with that of the first official courthouse. The new jail and courthouse were built at the same location as the first jail. Specifications for the jail included walls two feet in thickness, a dungeon with double grate windows, and a “good strong jail lock.”

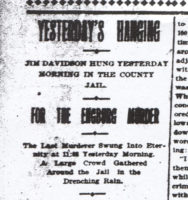

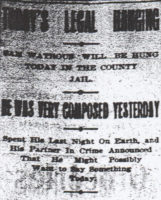

The county jail was built to hold murderers, robbers, petty thieves, vagrants and others who broke the law around Austin. It was also a place of execution for those who had been sentenced to die. Hanging was the method used for almost all executions in Texas until 1924. Under state law, hangings were administered by the county in which the trial took place, and it was the responsibility of the Sheriff to carry out the execution. Texas changed its execution laws in 1923, requiring the executions be carried out with the electric chair and that they take place at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville.

Those executed by hanging in Travis County included:

Lount (a slave), for murder and robbery, 7/25/1862

Meredith Haynes, for murder, 12/15/1871

George Barnes, for murder and robbery, 4/14/1873

Lawson Kimball, for murder and robbery, 4/14/1873

Taylor Ake, for rape, 8/22/1879

Ed Nichols, for rape, 1/12/1894

William Eugene Burt, for murder, 5/27/1898

Sam Watrus, for murder, rape and robbery, 10/27/1899

Jim Davidson, for murder, rape, and robbery, 11/24/1899

Henry Williams, for murder and rape, 5/2/1904

John Henry, for murder, 7/12/1912

Henry Brook, for murder, 5/30/1913

Inconvenient location and jail overcrowding were among the complaints that led to the construction of a new courthouse and jail in 1876. This jail was constructed at 11th and Brazos Streets, directly behind the new courthouse at 11th Street and Congress Avenue. The construction of the courthouse, jail, and jailor’s residence was financed by a local property tax increase and a state-approved bond election. The jail, which resembled a fortress, was two stories high and enclosed with two-foot walls made of solid stone. Each of the 24 cells measured 8 x 10 feet, and by a novel patent lever arrangement, all of the cell doors could be closed by the jailor without coming into contact with the prisoners. The jailor’s residence was connected to the jail by means of a long corridor.

The 1876 Travis County jail held some of Travis County’s better known prisoners. Billy Thompson, gunman, gambler and and younger brother of Ben Thompson, was held in the jail in 1876. Notorious gunmen and outlaws John Wesley Hardin and Johnny Ringo allegedly shared a jail cell in 1877. A more genteel inmate was William Sydney Porter. Later known worldwide as O. Henry, the short story writer spent time in the Travis County jail after being charged with embezzlement in 1898.

Chapter III: Prohibition

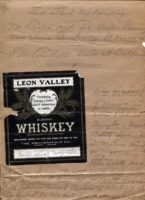

As settlers from the United States moved into the Mexican Texas, saloons were often some of the first establishments in new settlements. The pre-Civil War era was a period of especially liberal alcohol consumption in Texas. Although an 1845 Texas law banned saloons, it was rarely enforced and eventually repealed in 1856. The Texas Constitution of 1876 required the legislature to enact a local option law, which gave counties, cities and towns exclusive power to decide whether or not to ban alcoholic beverages within their borders. Over the years, many communities voted to become dry, while others narrowly defeated ballot initiatives to stay wet. By allowing counties and communities to prohibit liquor within their borders, local option laws succeeded in closing most of the legal saloons. However, many continued to operate illegally, particularly those in vice districts such as Guy Town.

Over the course of the 19th century, a movement which favored the elimination of vice and perceived immorality, often through legislative means, gained widespread support nationally. In Texas, public drunkenness was increasingly reported on as serious issue towards the end of the 19th century. Reports from the period indicated a public perception that drinking was a major cause of early deaths in the state, giving the temperance movement a stronger foothold. In the early 20th century, the prohibition movement advanced to convert a majority of the state's voters, and in 1919 Texas voters approved a state prohibition amendment which banned the sale, production, and transportation of alcohol. By 1920 most legal saloons in the state had been shut down and alcohol prohibition had come to dominate in Texas politics.

By 1925, opponents of prohibition were in control of the Texas government and refused to support enforcement. Nationally, popular support for prohibition receded dramatically after the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, and in 1933 the 21st Amendment repealed prohibition. In 1935, Texas voters ratified a repeal of the state dry law, and thereafter the prohibition question reverted to the local level, where it remains today.

Interested in learning more about early Travis County?

The archives is digitizing many of its most interesting records from early Travis County history. These records are being added to the Travis County Digital Archives, linked below. Of interest are 19th century inquest records and case files, including both from Austin’s most famous unsolved mystery, the Servant Girl Annihilator Murders. Please check out are digital collections and subscribe to our newsletter to learn when new records and media are added.