History of the Travis County Extension Service

This online exhibit is based on the 2014 Travis County History Day program, “Remembering Our Rural Roots: Extension Services in Travis County”. The exhibit provides an overview of the history of the Travis County extension services and the important programs they provide to the public.

Historical Overview of the Extension Service

Farmer

From the Edge of the Frontier to an Urban Metropolis: Growing from Travis County’s Rural Roots

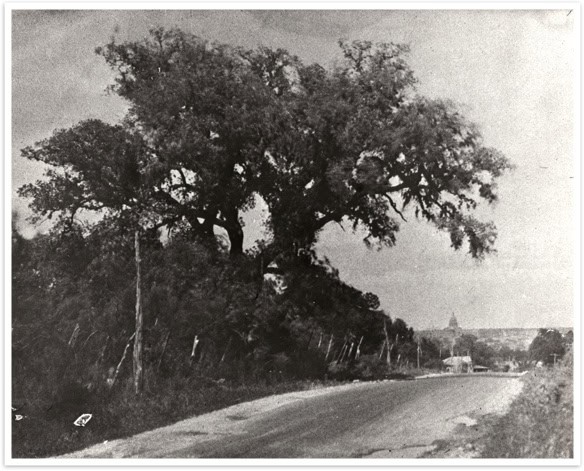

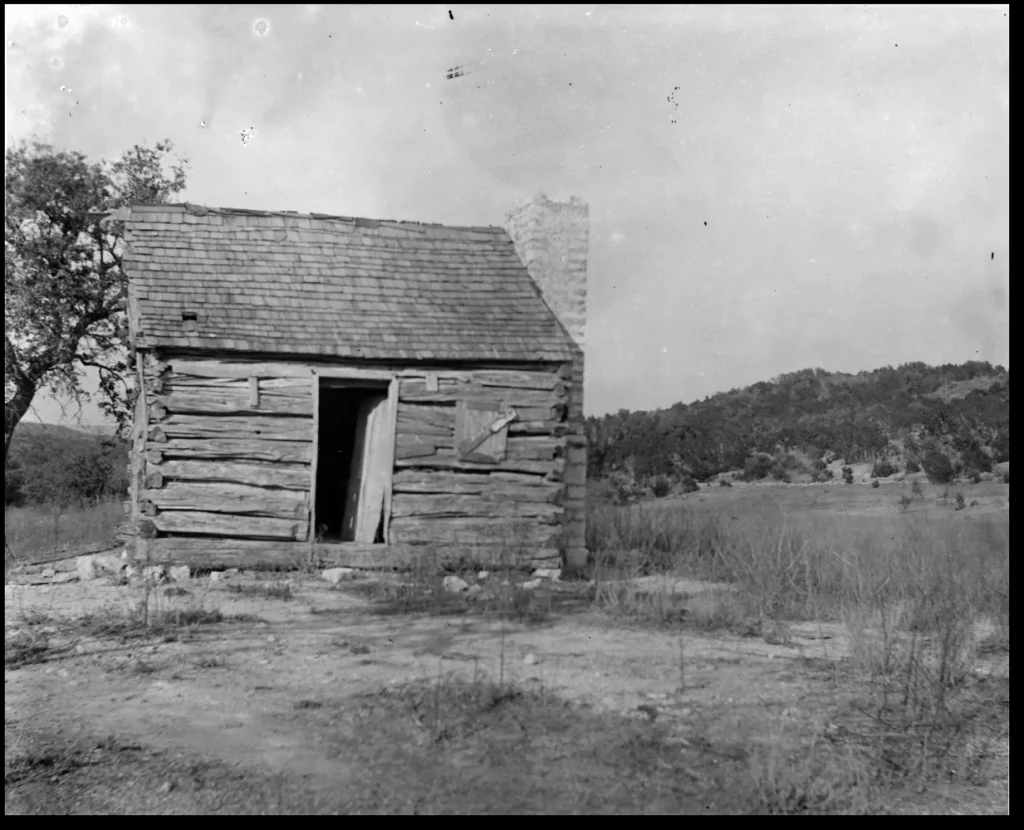

Travis County today hardly resembles the small community on the edge of the frontier it once was. Established in 1840, the county’s population at the time was mere 856 residents. This number grew rapidly in those early decades, and although the population of the city of Austin grew faster than the county, most residents lived in small communities outside the city. By 1890, Travis County’s population had grown to approximately 36,000 residents, less than half of which lived within the city of Austin. Even though Austin’s population continued to swell, by the turn of the century the majority of the county’s residents still lived on farms or in smaller towns, and agriculture dominated the area economy.

Such rural and agricultural-based communities were in mind when Congress approved the Smith-Lever Act in 1914, a federal law that established a nationwide cooperative extension service and provided for state-based agricultural services to benefit farms and communities. Extension services were essential in educating citizens and teaching skills in a variety of disciplines, to improve and enhance the quality of their lives. Even as the population within Austin surpassed the number of residents living in the county’s outlying communities, and as Travis County gradually transformed from a rural community to an urban one, extension services played an important role in the development and betterment of Travis County and its residents.

Texas Extension Services and the Smith-Lever Act

Extension services are educational programs implemented and designed to help people use research-based knowledge to improve their lives. The 1914 Smith-Lever Act encouraged state agricultural colleges to work cooperatively with other groups in providing extension services in the form of programs and demonstrations on a variety of topics, including agriculture and food, home economics, economic advancement, and youth development. Specifically, the Act stated as its purpose “to aid in diffusing among the people of the United States useful and practical information on subjects relating to agriculture, uses of solar energy with respect to agriculture, home economics, and rural energy, and to encourage the application of the same…”

The appropriation for the Cooperative Extension as established by Smith-Lever set up a shared partnership among the federal, state, and county levels of government to ensure support from each of the levels to help the system achieve stability and leverage resources. State land-grant institutions provided the administration for the extension programs.

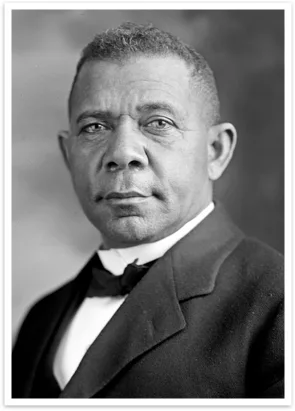

The unique nature of the Smith-Lever Act allowed for on-going extension education work that had been started in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by educators such as Seaman A. Knapp, A.B. Graham, Jane McKimmon, and Booker T. Washington. The move toward a model of cooperative extension education allowed for professional educators to be placed in local communities in order to improve lives.

“A demonstration is a practical, progressive example of good farming or home making which increases profit, comfort, culture, influence, power.” -Dr. Seaman A. Knapp

Under the Smith-Lever Act, the Texas legislature established what was then called the Texas Agricultural Extension Service, as well as the Cooperative Extension Program at Prairie View A&M University (originally the Alta Vista Agricultural and Mechanical College for Colored Youth). The legislature also passed laws authorizing county Commissioners Courts to provide and fund offices and conduct extension work in collaboration with the Texas A&M and Prairie View A&M extension programs. Soon, demonstrations, shows, and fairs became common throughout Texas.

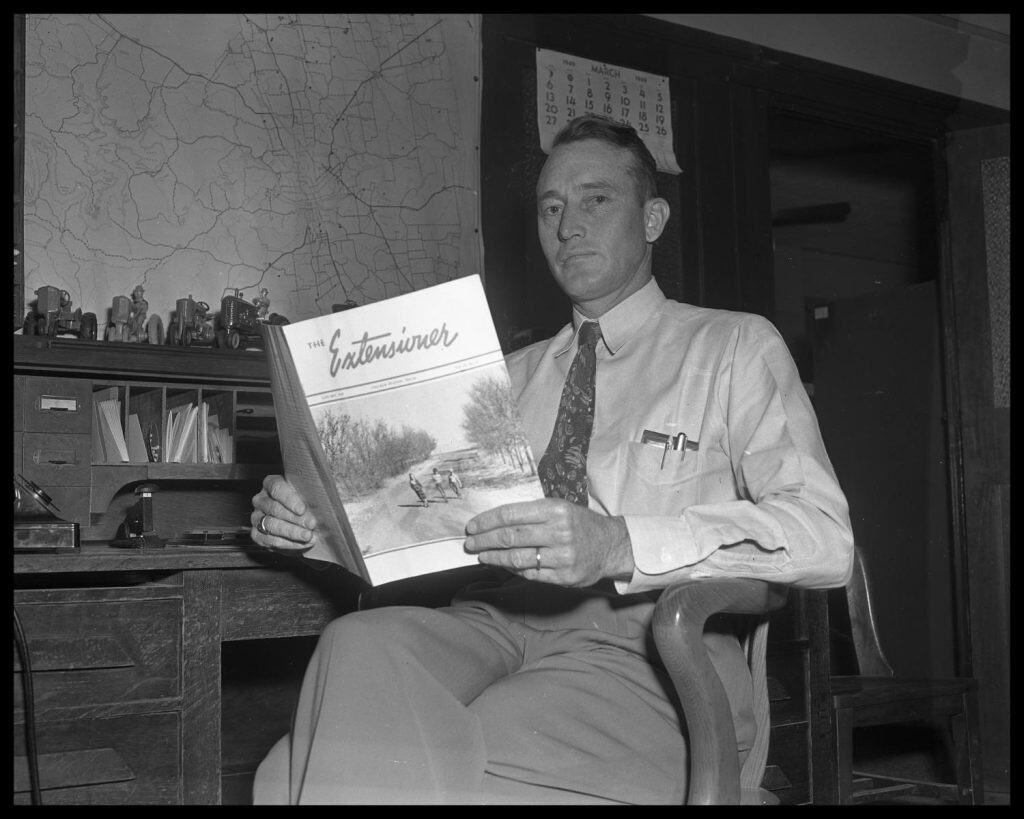

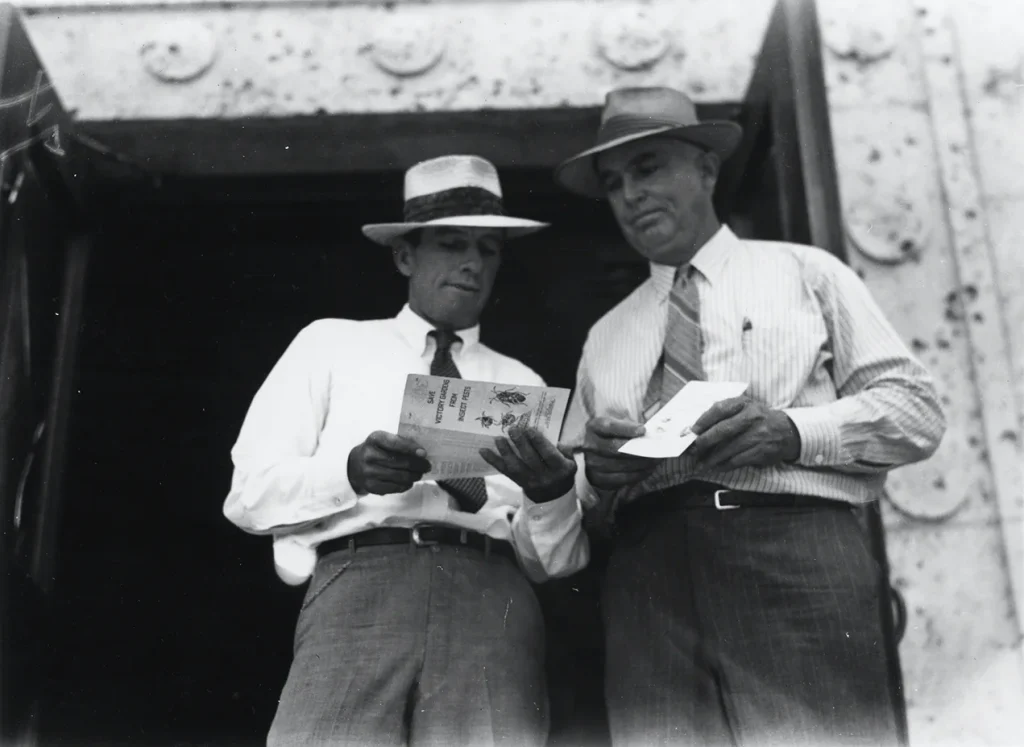

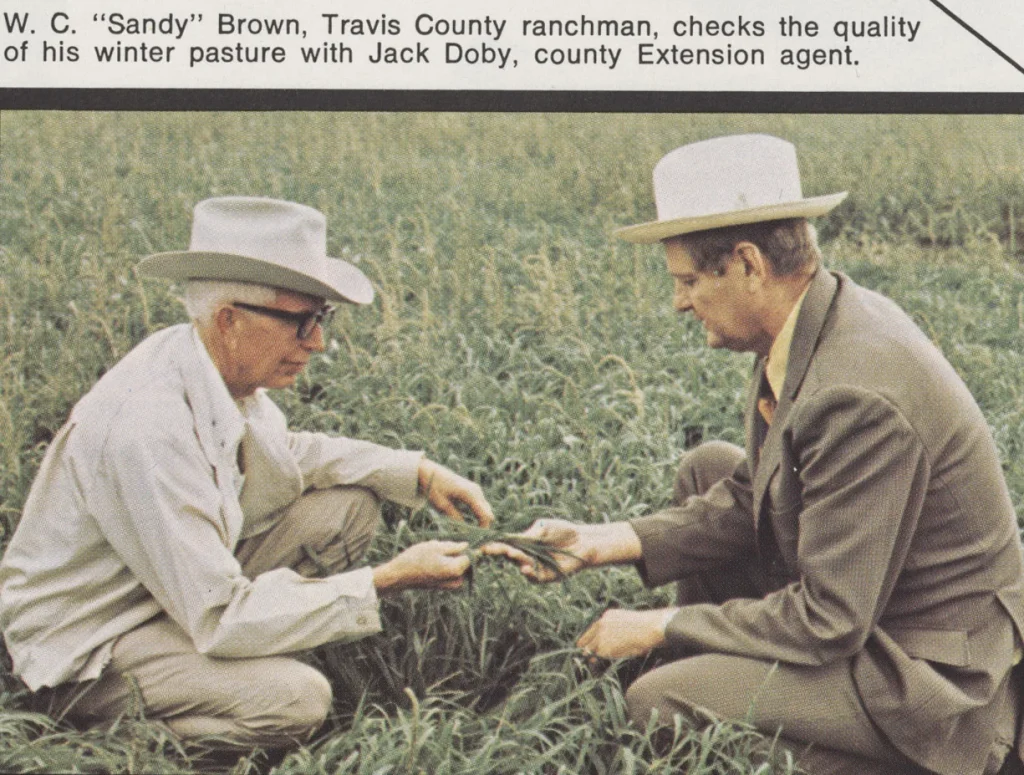

Within the extension programs, the most important person was the county agent, whose primary responsibility was teaching. His goal was to help people to have a higher standard of living and a more enjoyable life. During the 1920s and the Great Depression, Texas county agents taught adults and youth by means of conducting demonstrations.

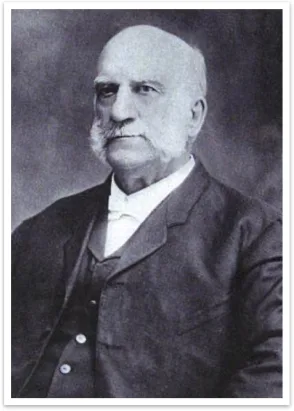

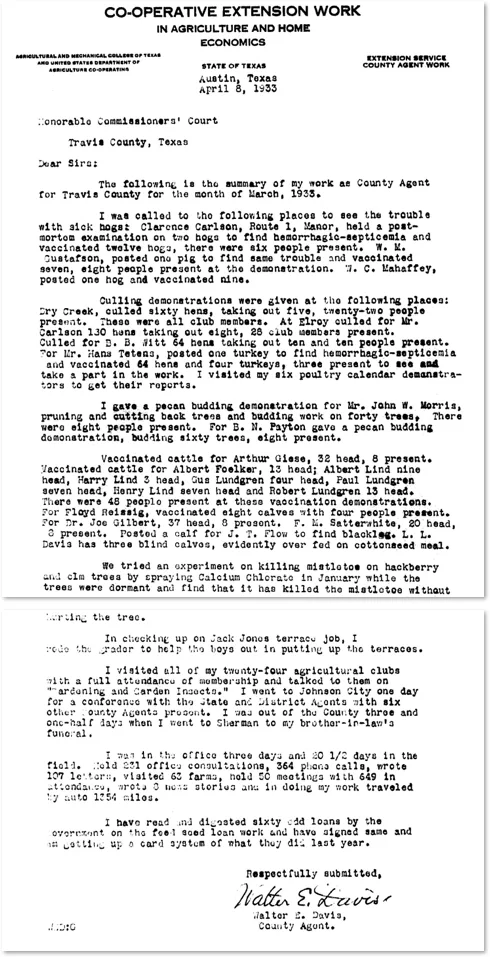

Walter E. Davis, First Travis County Extension Agent

Walter E. Davis began his work with Travis County as a Farm Demonstrator in 1911. In 1919, his contract was discontinued by the Commissioners Court, but upon petition by numerous residents and organizations, the Court approved the appropriation of funds for the annual salary of a County Extension Agent. In support of Mr. Davis and the continuance of his work were members of the Swine Breeders Association, Bee Keepers Association, Poultry Association, Dairy Association, Cotton Association, Sheep & Goat Association, Chamber of Commerce, Rotary Club, Lions Club, Kiwanis Club, and the Young Men’s Business League. As their petition to the Commissioners Court stated, “It is the unanimous opinion of this committee that the services of Mr. Walter E. Davis, who has been the Farm Demonstrator in the county for the past nine years, has not only been satisfactory in every particular, but we believe that his services in the county has been of untold benefit to the people of the county…”

Texas AgriLife Extension Service

The initial focus of the Texas Agricultural Extension Service programming was agricultural production, and specialists on staff included those in plant pathology, animal science, dairy science, poultry science, horticulture, and agricultural engineering. Rural Texans were encouraged to use new technology and produce food and fiber as efficiently as possible.

As times changed, so did the Extension Service programming. World War II brought about an emphasis on increasing food production, as extension staff encouraged farmers to meet production goals and adjust to shortages at home.

4-H clubs engaged in a large program to decrease livestock losses from disease and improper care. Over the years, important achievements were made by the Texas Agricultural Extension Service in a wide variety of additional areas, including tourism, swine production, aquaculture, wildlife management, pest management, adult leadership programs, and educational, financial, and health programs for minority and low-income Texans. Programming expanded to the ever-changing needs of the communities it served.

In 2001, the name of Texas Agricultural Extension Service was changed to the Texas Cooperative Extension, and in 2008, to the Texas AgriLife Extension Service. Today, the primary mission of the AgriLife Extension Service is to provide educational outreach programs and services to the citizens of Texas. Its goals include an increase in agricultural competitiveness, international marketing, public-policy education, agricultural safety and health, rural economic revitalization, water-use efficiency, water quality, proper use of chemicals in the environment, solid and hazardous waste management, conservation of natural resources, food safety, nutrition, care of the elderly, family economics and family relationships, literacy, and career development.

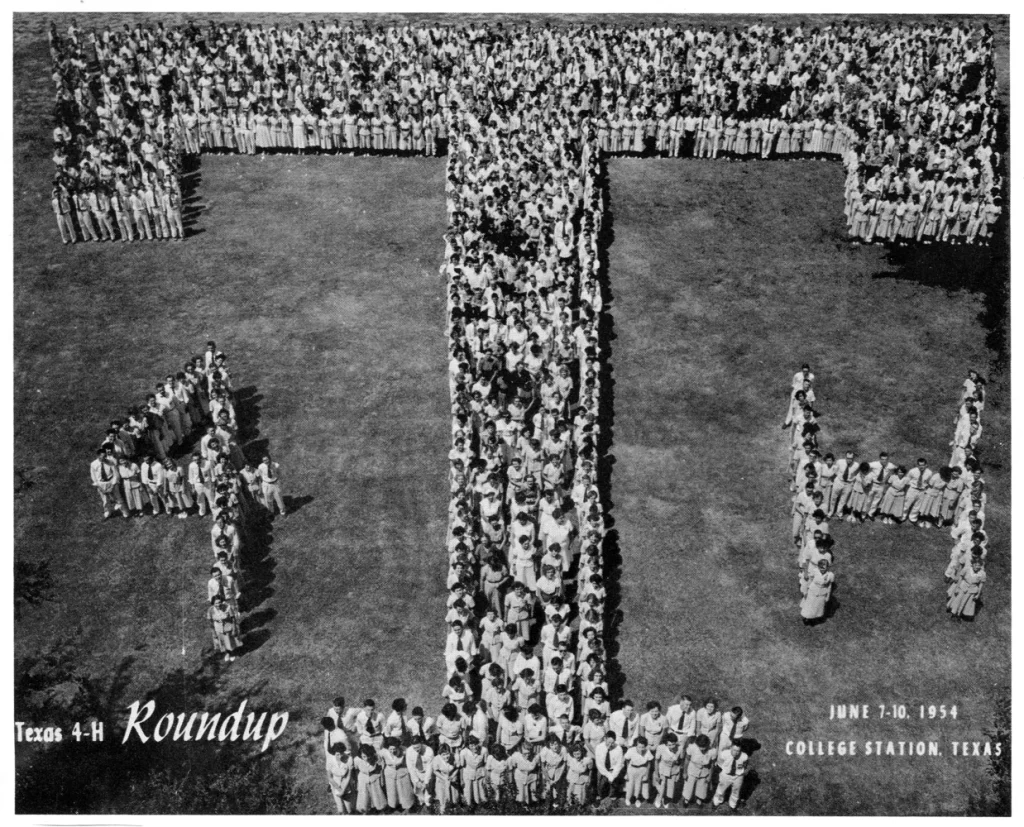

Texas AgriLife Extension is the largest extension service in the United States. It develops much of its own curriculum, which is then taught across the state through its network of over 600 county extension agents and nearly 350 extension specialists located in 250 of the 254 Texan counties. Together, these agents and specialists, with the aid of over 150,000 volunteers, educate the public through classes, publications, web sites, television series, and other outlets in the areas of agriculture, family and consumer sciences, human nutrition and health, environmental and natural resources, community development, and 4-H and youth development. The AgriLife Extension Service reaches over 15 million Texans annually, and the Texas 4-H program is the largest in the nation.

The AgriLife Extension Service in Travis County provides a high level of expertise in the following core service areas: 4-H and Youth Development; Agriculture and Natural Resources; Horticulture; Integrated Pest Management; Family and Consumer Sciences; and Nutrition, Health and Wellness. Their mission is to improve the lives of people, businesses, and communities through providing high quality, relevant outreach and continuing education programs and services to the residents of Travis County, and their goals include protecting the environment, developing youth, strengthening families, improving health, supporting agriculture, enhancing horticulture, and engaging communities.

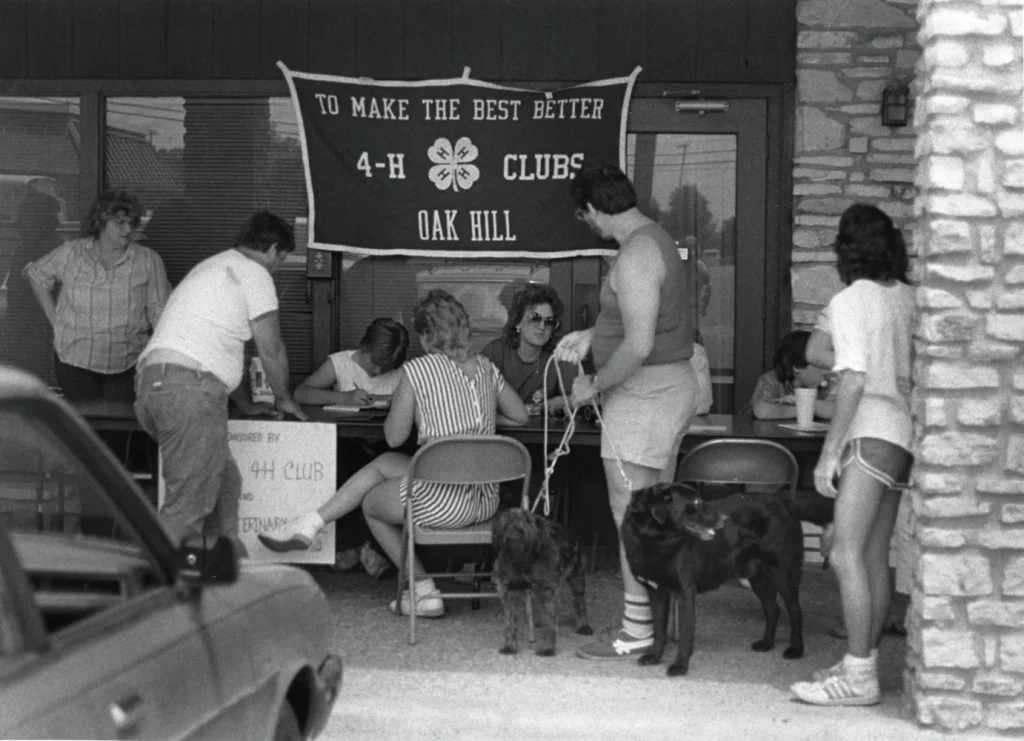

4-H – “To Make the Best Better”

4-H Pledge (1932 version):

My head to clearer thinking,

My hands to greater service,

My heart to truer loyalty and finer sympathy,

My health to efficient living in service to my home, my community, my country and my God.

4-H Creed (1978 version):

I believe in Boys’ and Girls’ 4-H Club Work for the opportunity it gives me to become a useful citizen.

I believe in the training of my HEAD for the power it will give me to THINK, PLAN and REASON.

I believe in the training of my HEART for the nobleness it will give me to be KIND, SYMPATHETIC and TRUE.

I believe in the training of my HANDS for the ability it will give me to be HELPFUL, SKILLFUL and USEFUL.

I believe in my Country, my State, my Community, and in my Responsibility for their development.

In all these things I believe and I am willing to dedicate my efforts to their fulfillment.

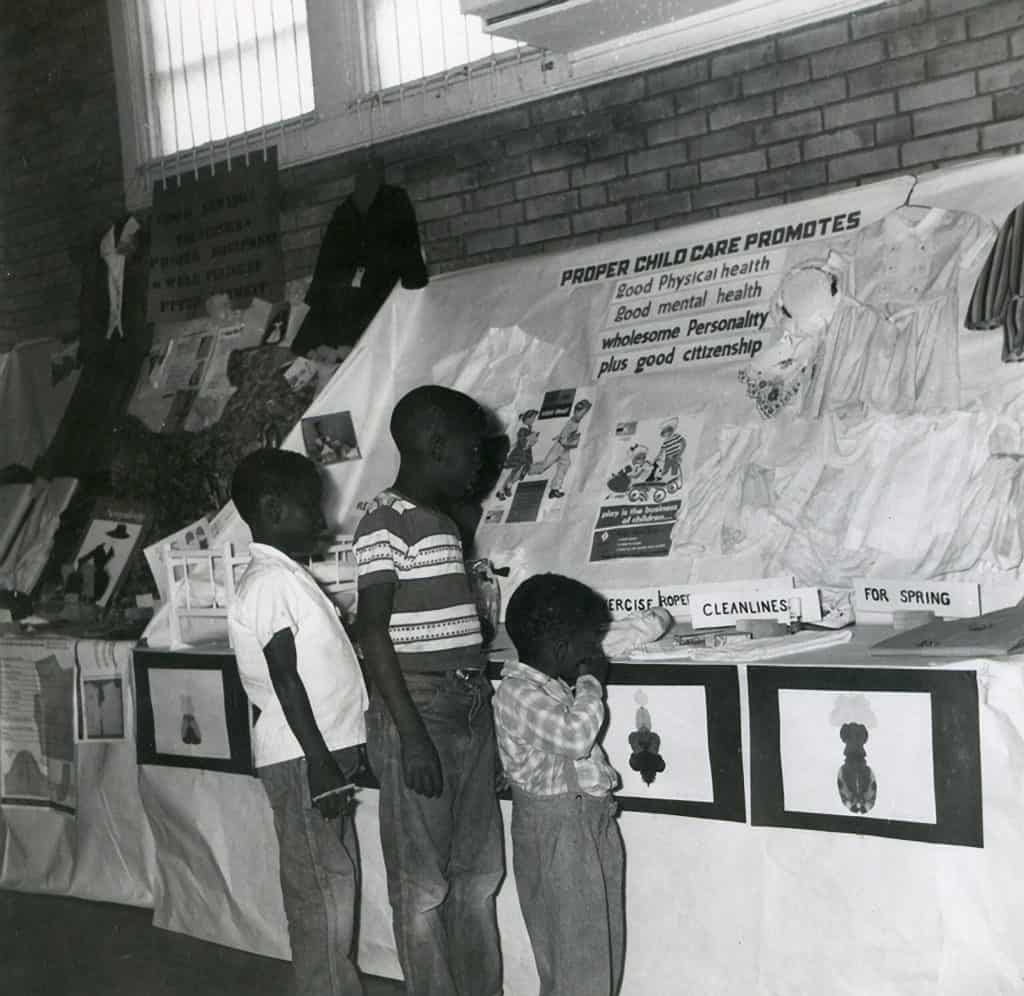

Since its inception more than 100 years ago, 4-H has become the nation’s largest youth development organization. The impetus behind 4-H was to help young people and their families gain the skills needed to be proactive forces in their communities, to develop ideas for a more innovative economy, and to connect public school education with rural life. 4-H opened the door for youth to learn leadership skills and to experience practical, hands-on learning experiences outside the classroom.

Community youth clubs, the precursors to 4-H, were initially begun to share agricultural advances with rural communities through young people. In the late 1800s, researchers at experiment stations of the land-grant universities found that adults in farming communities did not readily accept new agricultural discoveries. However, educators discovered that youth were willing to experiment with these new ideas and then share their experiences and successes with the adults.

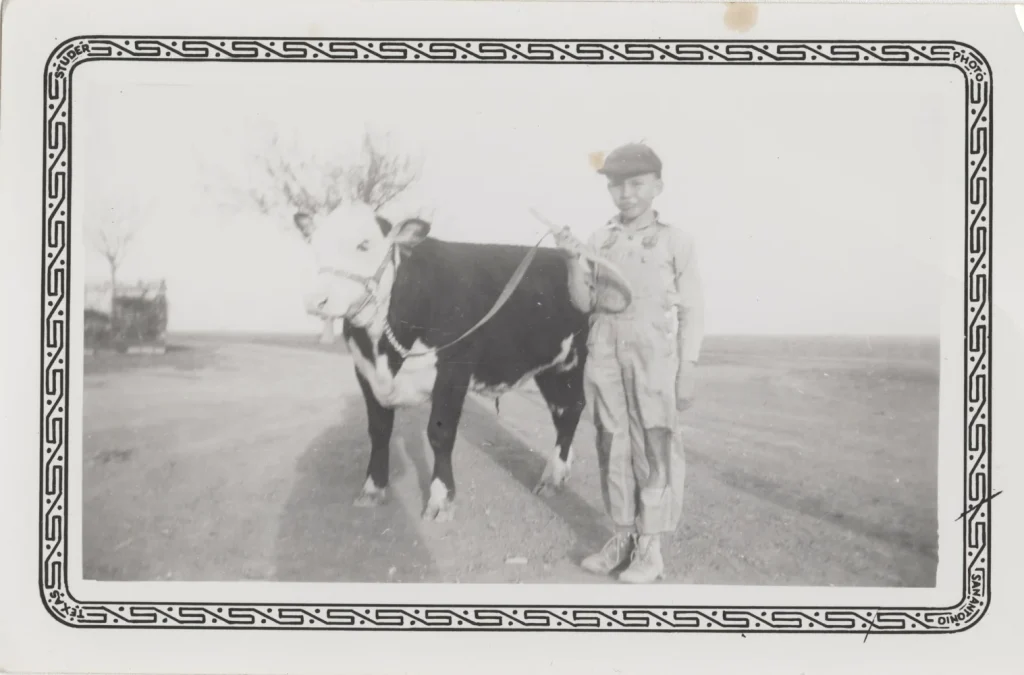

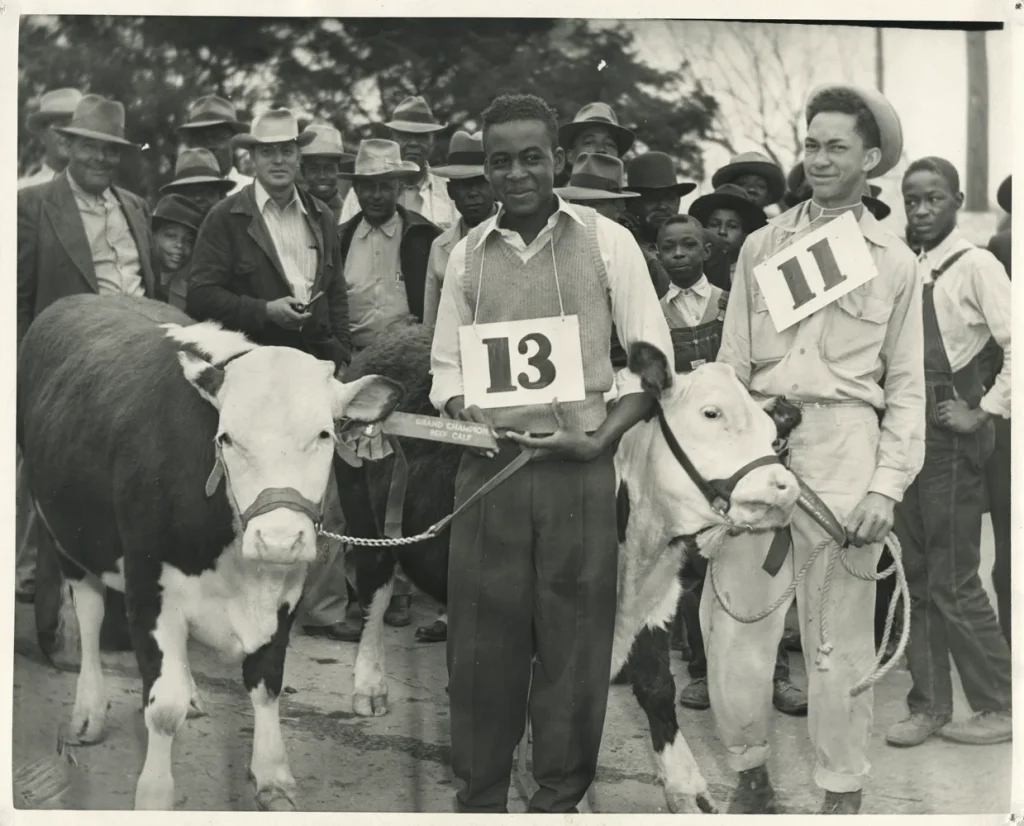

One of the earliest such programs was founded in 1902 in Clark County, Ohio, when agriculture extension agent A.B. Graham started youth clubs called the “Tomato Club” and the “Corn Growing Club.” Local agricultural after-school clubs and fairs were began in Minnesota that same year, and soon, numerous other youth clubs, such as “pig clubs” and “beef calf clubs,” among many others, were being established throughout the country and in nearly all states.

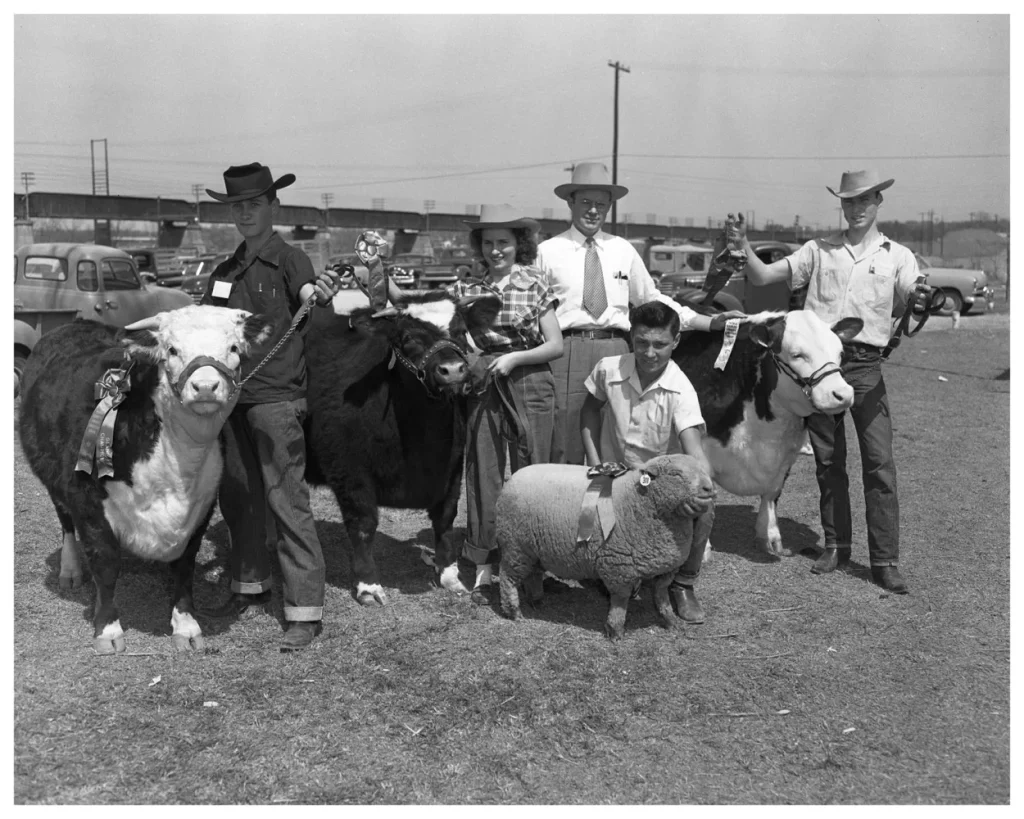

The first such club in Texas, a “Corn Club” for boys, was established in Jack County in the fall of 1907. The purpose of this club was to teach boys new practices for raising corn that the farmers, their fathers, would not adopt. By 1912, these youth clubs were known as 4-H clubs. The clover emblem, with an H on each leaf (standing for head, heart, hands, and health), had been adopted the prior year. The national 4-H organization was formally established soon after in 1914, with the passage of the Smith-Lever Act.

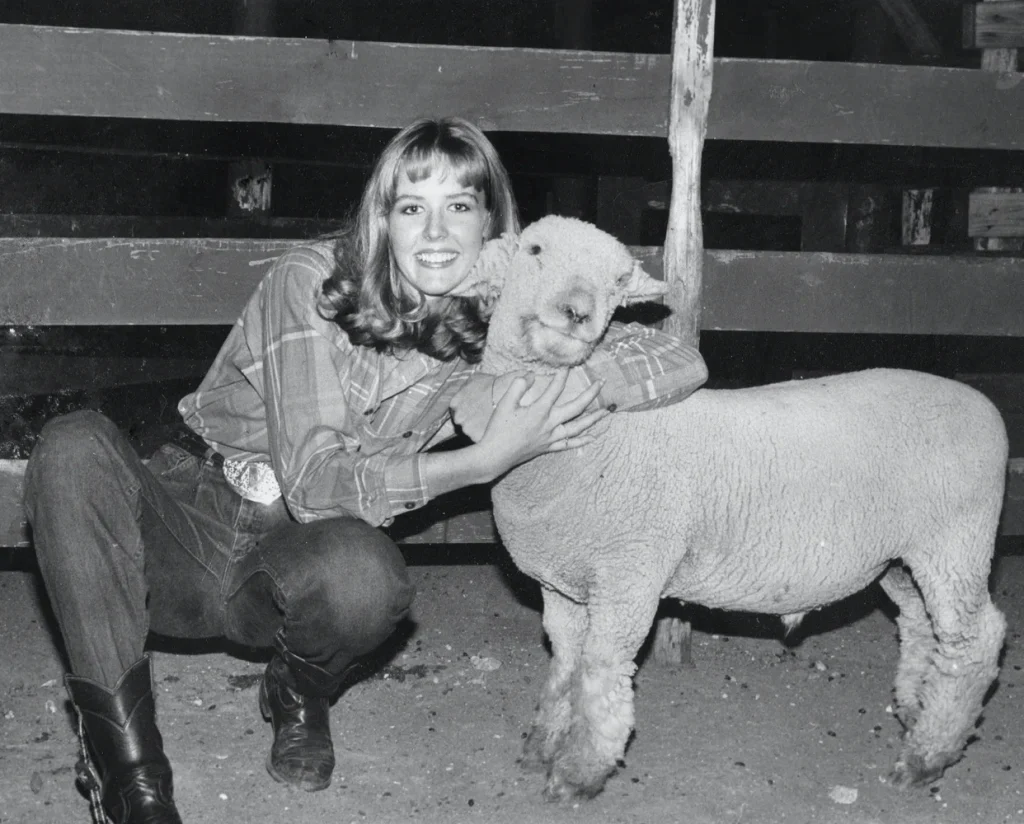

The Act included within the Cooperative Extension Service charter the work of various boys’ and girls’ clubs involved with agriculture, home economics and related subjects. Although different activities were emphasized for boys and girls, 4-H was one of the first youth organizations to give equal attention to both genders.

Proficiency in areas such as leadership, communication, and decision making were built into 4-H projects, activities, and events to help participants become contributing, productive, self-directed members of a forward-moving society. The passing decades saw further program and organizational coordination. In addition to the core 4-H community club model, youth could participate through urban groups, community resource development, special interest groups, nutrition programs, school enrichment, camping and interagency learning experiences.

Following World War I, the 4-H organization underwent further formalization. The general structure of local clubs was firmly established, an expansion of projects was encouraged, relations between club work and vocational education in the schools were defined, and the general principle of local initiative was ratified. Membership continued to grow and new clubs were established across the nation – by 1943, the number of youth participating in 4-H had reached 1.6 million. As 4-H began to expand into urban areas, new programs were added; although agriculture had been the primary focus at the beginning, 4-H began to emphasize life skills, personal growth, and lifelong learning in a multitude of areas.

4-H continues to thrive and expand today as one of America’s foremost youth development initiatives. While constantly continuing to change in support of the evolving needs of young people today, most of the original concepts and philosophies – the proven strengths – remain unchanged. 4-H creates opportunities for urban, suburban and rural youth to develop into mature adults and engaged citizens through partnerships with caring adult volunteers and staff.

Today, 4-H reaches additional youth through the 4-H CAPITAL program, which provides high quality after-school enrichment programs that focus on science, engineering and technology with hands-on learning experiences. 4-H CAPITAL began in 1992 as a 5-year USDA grant. Adopted by Travis County in 1997, the program received its first AmeriCorps grant in 2003, and since then, AmeriCorps funding has been continuously renewed annually. With the support of AmeriCorps volunteers, 4-H CAPITAL has grown from one school to 30, totaling more than 25,000 contact hours annually with Travis County youth.

Using the latest advancements of the country’s land-grant colleges and universities, 4-H’ers participate in learn-by-doing projects, group meetings and exhibits that focus on healthy lifestyles, citizenship, and science, engineering and technology. They tackle some of the nation’s top issues, from global food security, climate change and sustainable energy to childhood obesity and food safety.

4-H out-of-school programming, in-school enrichment programs, clubs and camps also offer a wide variety of opportunities – from agricultural and animal sciences to rocketry, robotics, environmental protection and computer science – to improve the nation’s ability to compete in key scientific fields and take on the leading challenges of the 21st century.

Horticulture

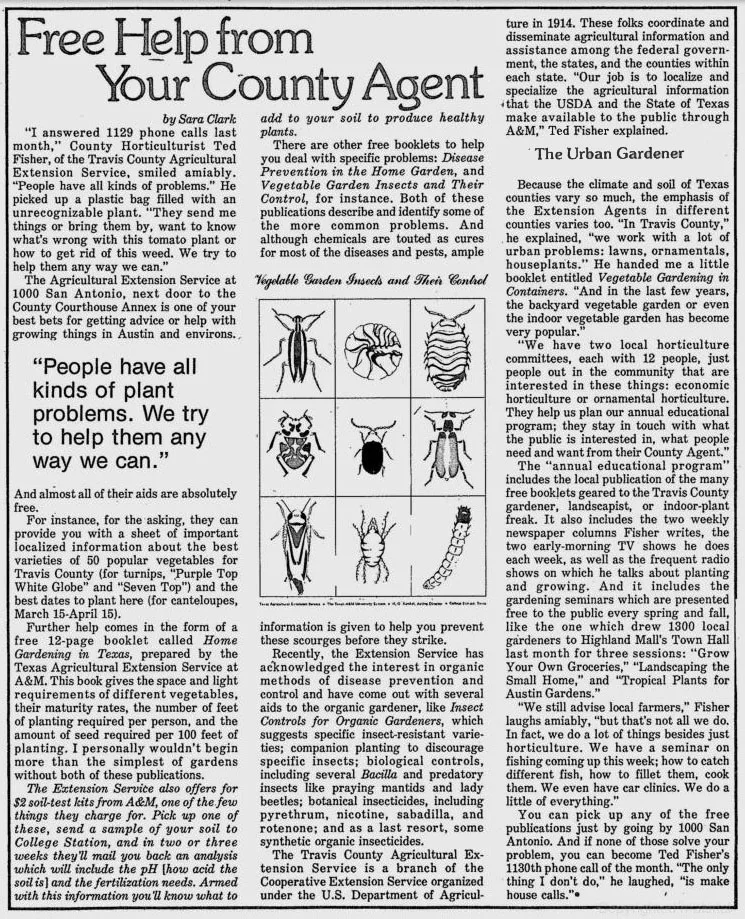

Horticulture is the science and art of producing, improving, marketing, and using fruits, vegetables, flowers, and ornamental plants. Texas A&M’s Agricultural Extension program began offering horticulture resources in response to overwhelming demands for such information.

The A&M Extension horticulture programs promote research-based horticultural practices that help residents create beautiful, productive gardens and landscapes while conserving water and other natural resources. They also support local food producers and the green industry with educational programs to help make their farms and businesses more profitable.

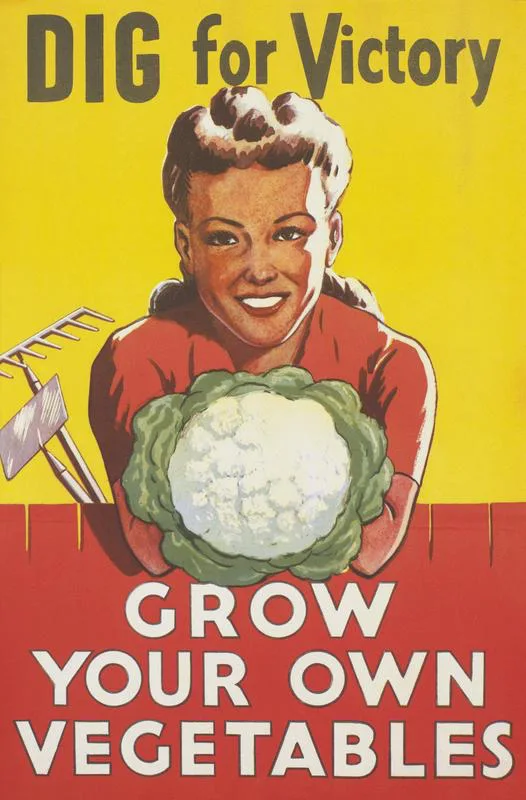

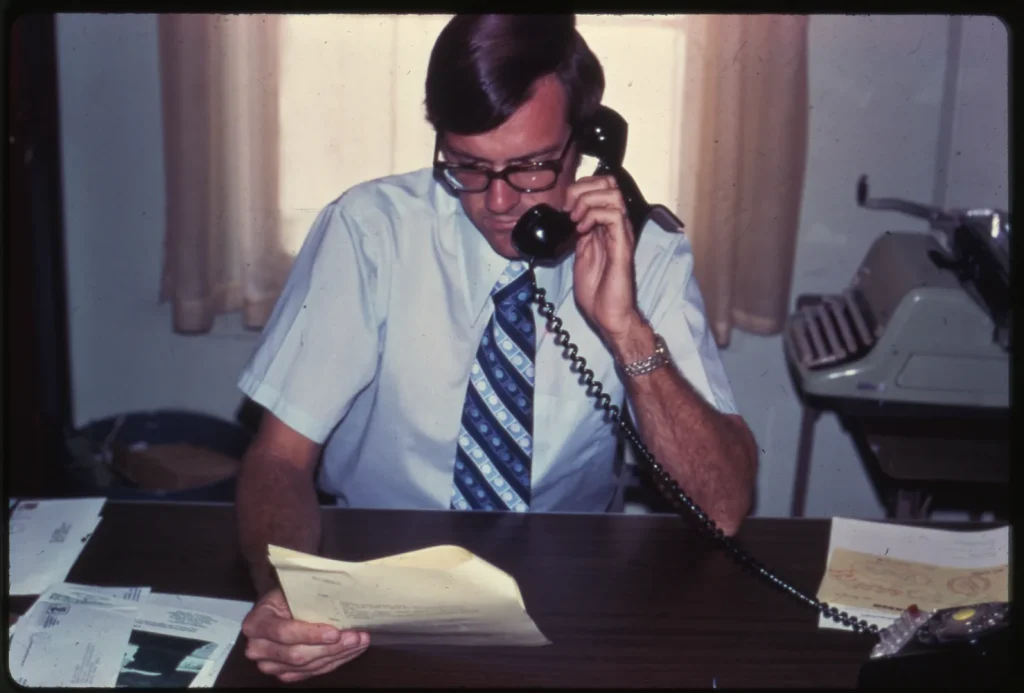

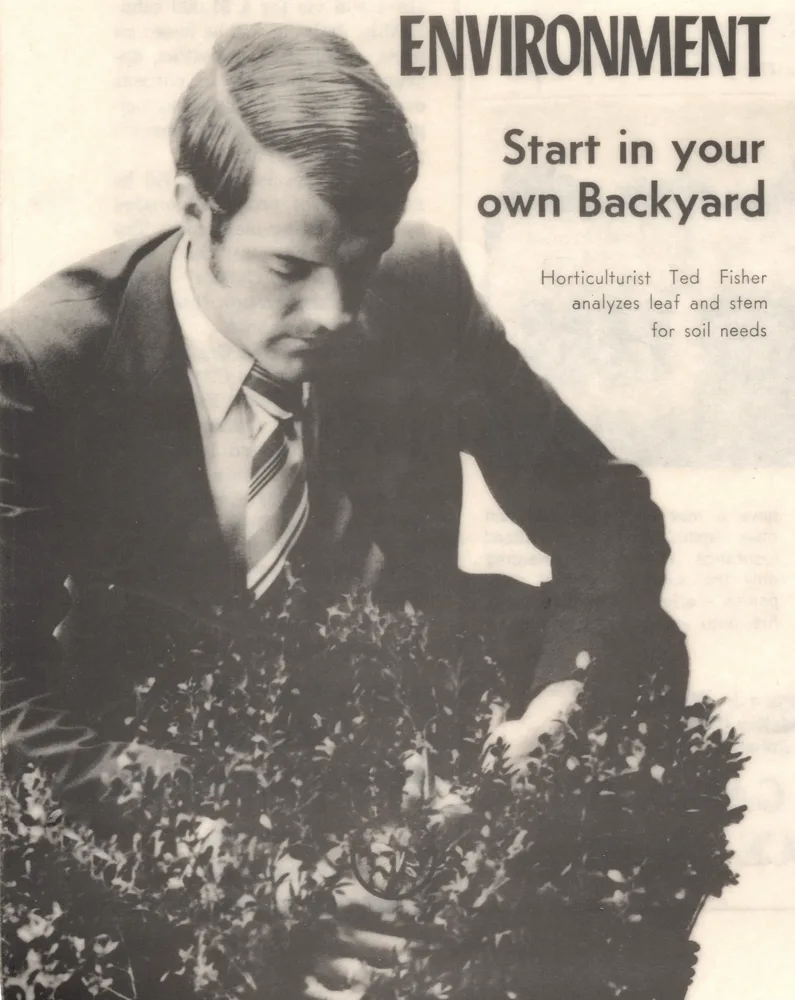

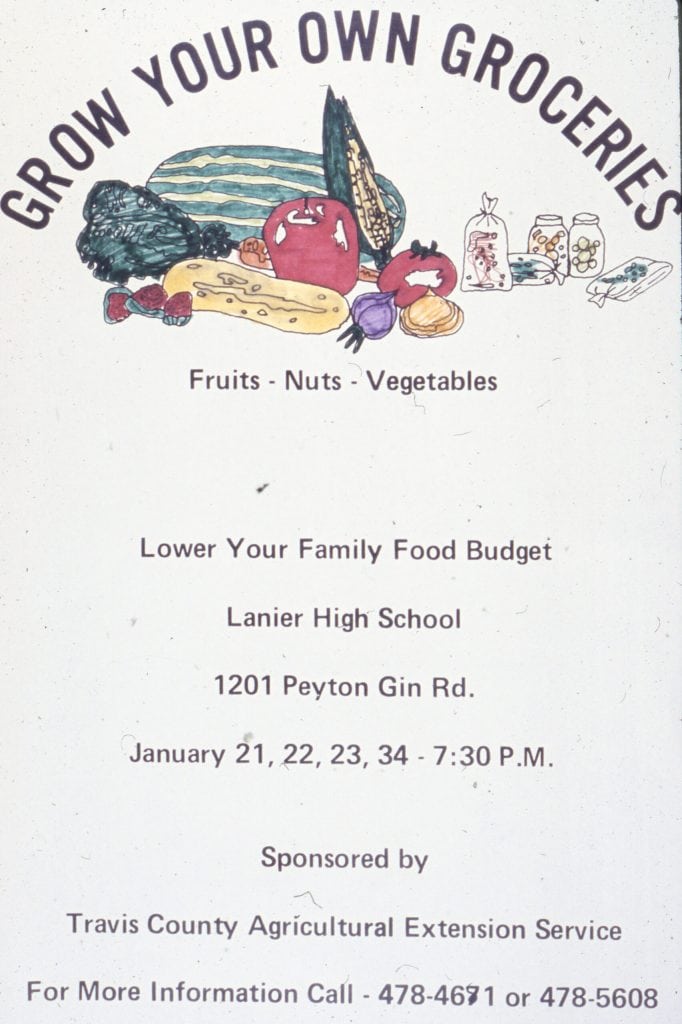

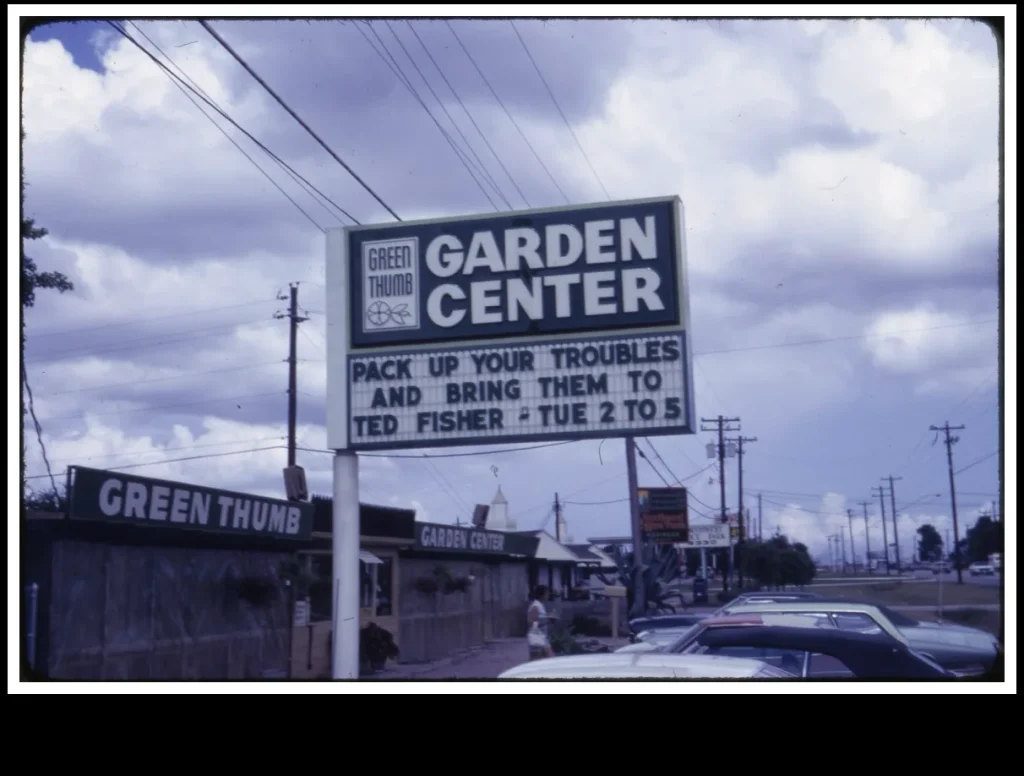

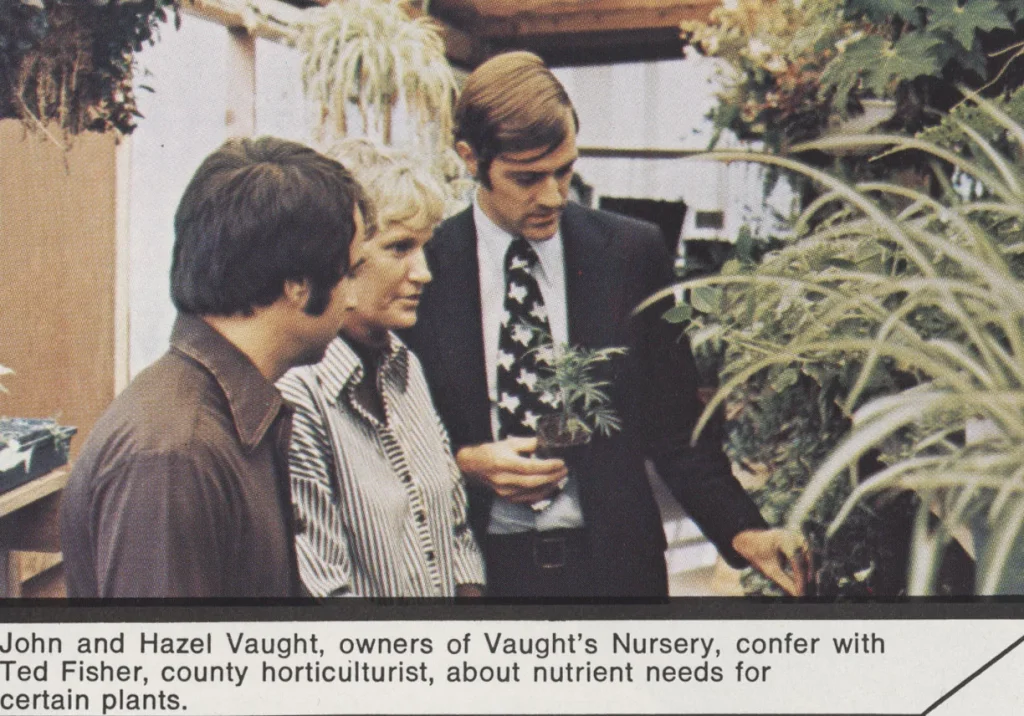

The Texas A&M Extension Horticulture program in Travis County was established in 1969, under the guidance of horticulturist Ted Fisher. Although the program had few staff members at the beginning, the demand for information was great and phone calls were frequent. Resources available at the time included information on topics such as home gardening in Texas, popular vegetables for Travis County, backyard vegetable gardens, and houseplants. Programs such as “Grow Your Own Vegetables” and “Tropical Plants for Austin Gardens” drew hundreds of local gardeners.

Today, the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension horticulture program in Travis County continues to offer a wide spectrum of literature, practical resources, workshops and events, to encourage local interest in environmental stewardship and home gardening. The Travis County program includes the following components: Home Garden & Landscape; Urban Agriculture; Green Industry; Youth Gardening; Ground to Ground; and, the Master Gardeners.

Home Garden and Landscape

The Home Garden and Landscape program offers knowledge and resources regarding home landscape and gardens, including maintenance efforts and tips for increasing environmental sustainability. This program covers a variety of topics, including edible gardens (fruits, vegetables, nuts, and herbs), landscapes and lawns, trees and ornamentals (such as shrubs), and managing plant problems (including weeds, pests and disease).

Urban Agriculture

In 2008, the USDA’s Census of Agriculture data revealed historical growth in small acreage farming operations, hinting at major transformations underway in food systems across America, including in Central Texas.

n recent years, the number of local farmers’ markets, farm stands, CSA (community supported agriculture) subscriptions, and school gardens have multiplied in Travis County. With this focus on fresh foods and sustainability, many residents are transforming yards into gardens, some complete with fruit trees, layer chickens, and honey bees. In step with this local food movement is some residents’ interest in producing food for sale through sustainable or organic small acreage farming operations.

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension in Travis County supports the important role that small-acreage farmers hold in in the local community, economic, and food-system development. The program works to connect farmers to the vast, science-driven knowledge of Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, and builds a robust set of educational resources for both current and aspiring urban farmers in Central Texas.

Green Industry

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension has an array of resources for green industry professionals, including guidebooks on managing greenhouses, economic fact sheets for Texas green industry, guidelines for ornamental plant care and merchandising, publications on environmental best practices, and template nursery employee safety training programs and policies.

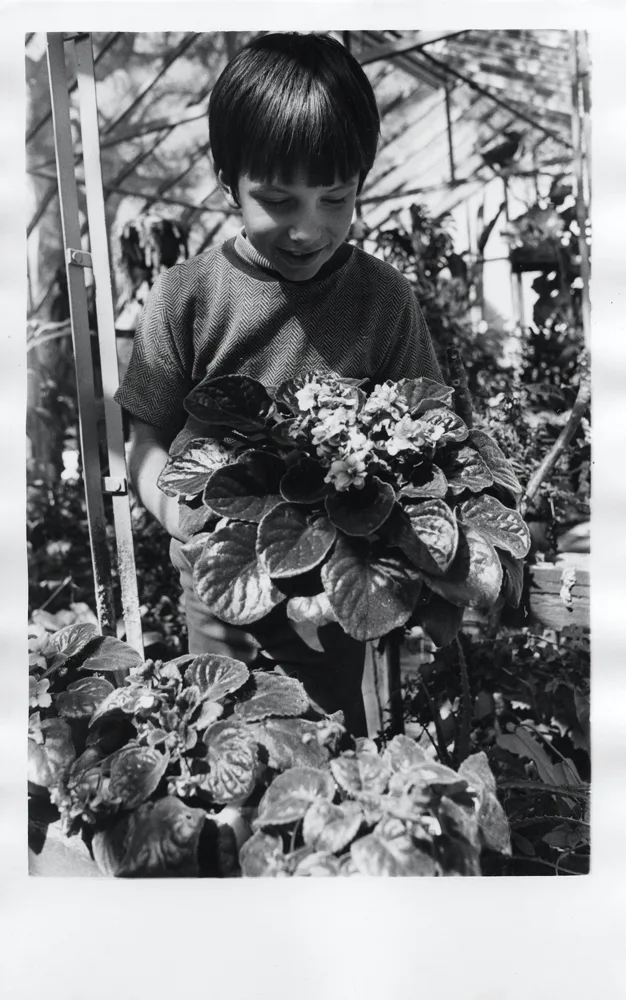

Youth Gardening

The AgriLife Extension Horticulture program in Travis County includes teaching gardening to youth through Capital 4-H afterschool gardening programs, and working with the Sustainable Food Center to provide wrap-around training, resources, and mentorship to school garden programs in Travis County.

Ground to Ground

Ground to Ground is a city-wide campaign that diverts nutrient-rich coffee grounds from landfills and puts them back to work in local residents’ yards, farms, and gardens. A partnership between Texas A&M AgriLife Extension-Travis County and Compost Coalition, Ground to Ground is simple, sustainable, and community-driven.

Any resident can pick up free buckets of post-brew grounds to use at their residence or community garden. The only commitment required is to rinse and return the bucket to the business.

Travis County Master Gardeners

The term “Master Gardener” was first coined in the early 1970s to describe a new Extension program in Washington State, and it has since spread into Texas and blossomed into one of the most effective volunteer organizations in the state.

The Texas Master Gardener program had its beginnings in 1978 with Extension horticulture training at Texas A&M University. At that time, county agents in the Texas Cooperative Extension were experiencing overwhelming demands for horticulture information. The first Master Gardener class was held in 1979 in Montgomery County, and by the end of the 1980s, eight Texas counties had Master Gardener programs. The Texas Agricultural Extension Service made an official commitment to a Texas Master Gardener program in 1987 with the hiring of a statewide coordinator. In the 1990s, the Texas Master Gardener movement exploded, fueled by the program’s success and visibility, and by 1998, there were 54 county Master Gardener programs with over 4,000 certified Master Gardeners statewide.

Master Gardeners are members of the local community who take an active interest in their lawns, trees, shrubs, flowers and gardens. They are enthusiastic, willing to learn and to help others, able to communicate with diverse groups of people, and have special training in horticulture. Master Gardeners complete 50 hours of intensive training and a year-long internship in order to offer research-based horticultural information and advice to their community.

Instruction covers topics such as botany 101, landscape design, native and adapted plants, tree selection and maintenance, turf grass, propagation, vegetable gardening, soil science, entomology, plant pathology, composting, fruit and nut crops, and water conservation. In exchange for their training, Master Gardeners contribute time as volunteers, working through their local Extension office to provide horticultural-related information to their communities.

The size of programs varies from as little as one to as many as 478 Master Gardeners. The Master Gardener program’s strength lies in its ability to meet the diverse needs of the individual communities it serves. By combining statewide guidelines with local direction and administration, the program offers the flexibility necessary to keep it a vital and responsive organization that serves all of Texas.

The Travis County Master Gardener Program was established in 1993 by Extension agent Ted Fisher to assist in the dissemination of research-based horticultural and environmental knowledge, through publications, services, and continuing education, to the citizens of Travis County. Highly successful and rapidly growing, in 2010 the Travis County Master Gardeners had 225 volunteers, consisting of both master gardeners and interns. Approximately 30 new applicants are accepted each year.

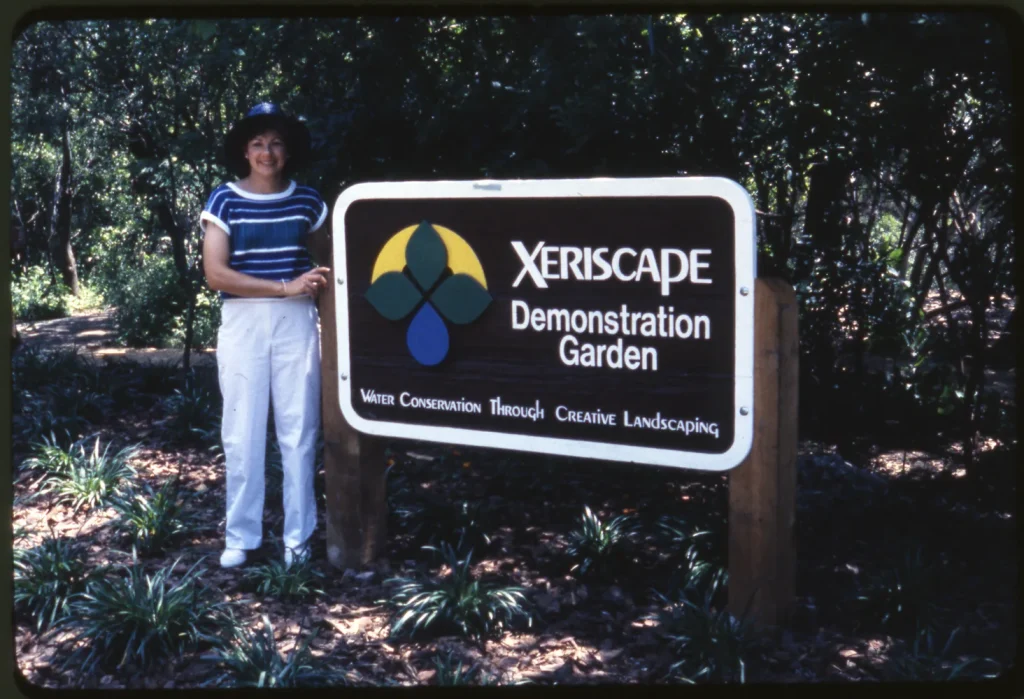

Today, the Travis County Master Gardeners provide a variety of free services to the public, including public lectures on gardening topics held at different locations in the county. Educational seminars include lectures by Master Gardeners and other local experts on seasonal topics, providing up-to-date, sound gardening advice for homeowners. A demonstration garden, located at the Travis County AgriLife Extension Office, serves to demonstrate to the public recommended native and adapted plants and growing techniques. Throughout the year, the Travis County Master Gardeners also provide community service with free information at plant clinics held at public events around the county, tours, and a help desk, where volunteers provide free gardening advice to homeowners over the phone, by email, and in person.

Family and Consumer Sciences

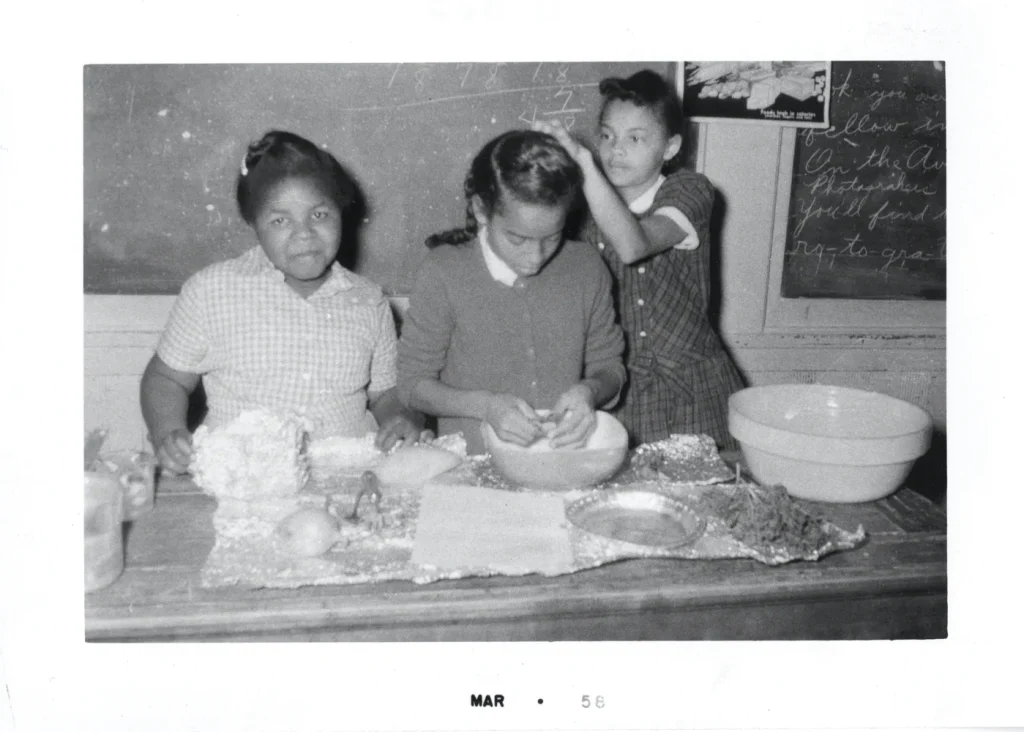

Home demonstration work began in Texas for the purpose of teaching rural girls homemaking skills, primarily in the areas of food production and preservation. In 1914, agricultural and home economics demonstration efforts were formalized with passage of the national Smith-Lever Act, which led to formation of the Texas Extension Services—the forerunners of today’s Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service and the Prairie View A&M Cooperative Extension Program.

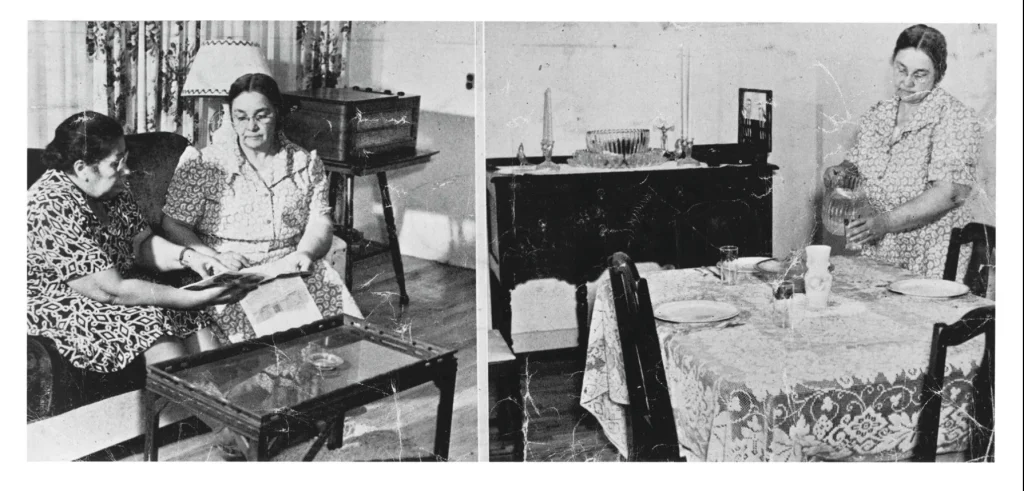

From the beginning, Extension education relied on home demonstrations, which evolved into outreach on subjects that are known today as Family and Consumer Sciences. These subjects include raising children, housing and environment, eating well, managing money, and staying healthy.

Although home demonstration work in Texas preceded the Smith-Lever Act, the movement benefited greatly from the state and local government funding that resulted from the act. A state superintendent for girls’ clubs was appointed, and home demonstration work expanded to include assistance in clothing, home improvement and management, and family living.

By 1917, rural Texas women had joined girls in home demonstration work. Because food production and preservation were the initial focus of home demonstration, the program was utilized in the food- conservation programs of World War I. After the war, demonstration work advanced, with an increased number of county agents and staff specialists added in several areas.

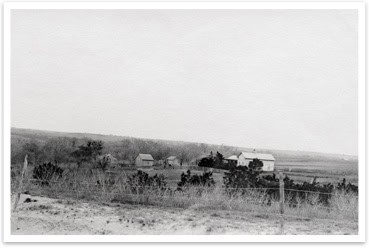

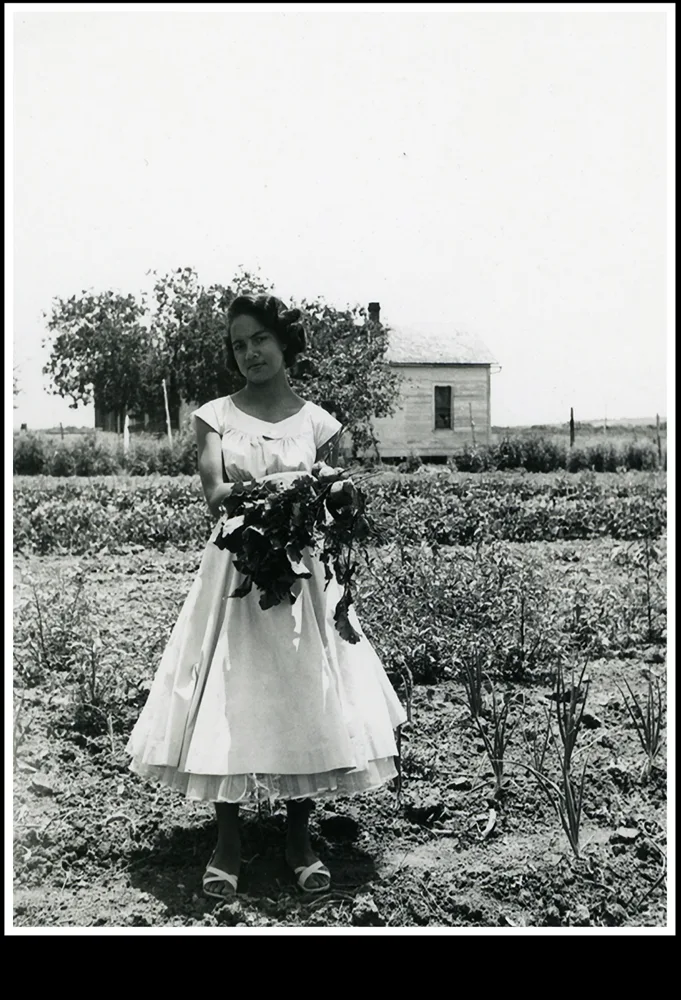

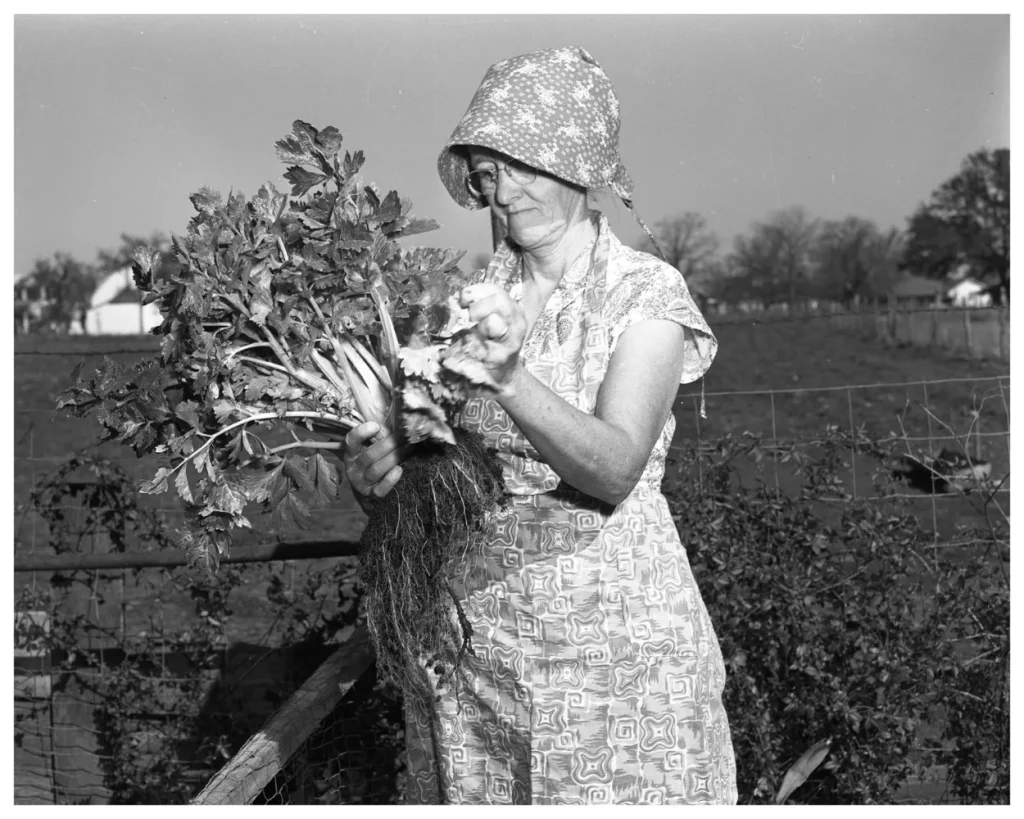

Women in rural Texas not only were expected to raise children, cook, and do household chores; their work also often included planting and tending the family vegetable garden, preserving the family’s food, and raising poultry to sell or prepare for the family table.

Through the first half of the 20th century, home demonstration agents went to homes throughout the state and provided practical demonstrations and advice on vegetable gardening, canning, sewing, cooking, household management, family health, poultry-raising and other aspects of daily life. These demonstrations were often some of the only ways that women in rural Texas could acquire the information and skills needed to improve their lives.

Opal Washington

Opal Washington was born in Crockett, Texas, in 1925. A graduate of Prairie View A&M University in 1944 with a degree in home economics, she began working with African-American families in Lee, Bastrop, and McLennan Counties in home extension work before coming to Austin in 1952. Mrs. Washington served the home extension needs of Travis County’s African-American community for many years, and she continued working in the home extension program after it was desegregated in 1965. She was a major figure in African-American education and home economics in Travis County, and she wrote numerous articles on the topics of cooking and raising vegetables. After her retirement in 1982, Mrs. Washington edited cookbooks and continued her work in home economics education. She died in Austin in 1997.

As the 1927-1928 Travis County Community Clubs Yearbook stated, “the primary aim of the study of Home Demonstration Clubs of Travis County is to stimulate interest in home-making; to develop ideals of true economy and thrift through systematic conservation, and elimination of needless waste; to encourage home industries through gardening, poultry raising, and dairying, thereby increasing food production; to develop leadership for community life; in a word, to develop in women and girls a new enjoyment and satisfaction, that we may find in our home environment and community life more happiness.”

Membership for home demonstration clubs grew steadily in Texas, from 152 clubs in 1917 to 2,268 clubs in 1934. In 1937, more than 14,000 rural black women were also home demonstration participants. Home demonstration work in Texas reached an all-time high in the 1940s, with more than 57,000 women belonging to about 3,000 women’s demonstration clubs throughout the state.

Early home demonstration agents were often viewed as community role models due to their knowledge and self-sufficiency. In their demonstrations and teachings, agents’ techniques stressed efficiency, comfort, beauty, and cleanliness. They emphasized the sense of production and accomplishment achieved through happy homes and prosperous communities. As times changed, home demonstration agents adapted and taught the knowledge and skills needed to help families function more effectively and efficiently using their own resources and strengths. As Dr. Jennie Kitching, retired AgriLife Extension associate director for human sciences said, “The value of the home demonstration agent to Texas history cannot be calculated. They were instrumental in the development of a middle class in the state, as their work was vital in showing families how to improve their everyday lives.”

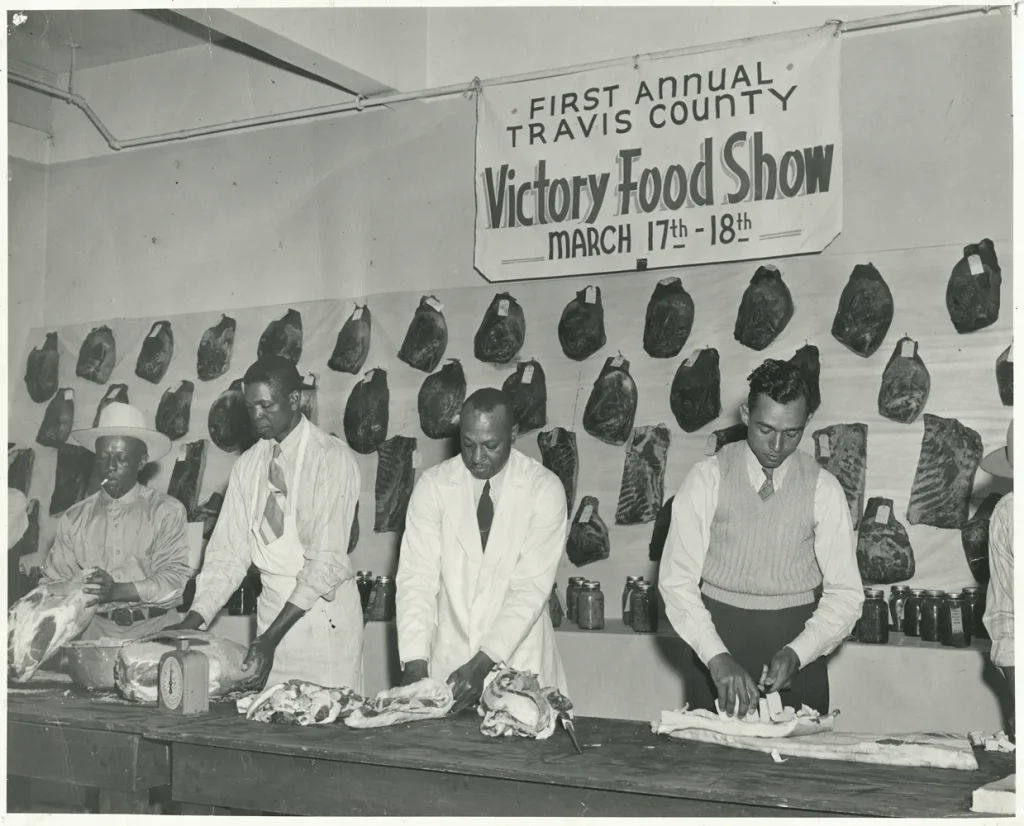

During World War II, efforts were again enlisted for such patriotic food-related causes as “victory gardens” and “victory canning.” In the 1950s, as more women were employed and fewer families lived in rural areas, programs placed emphasis on giving scholarships and enabling women to develop leadership skills. Subsequent decades continued to focus on family issues, but with a wider breadth of programming. Topics included the improvement of senior care, the effect of policies and legislation on families, furthering adult education, children’s car seat and seat belt safety, training of women to assume leadership and teaching roles, and environmental issues.

Today’s Family and Consumer Sciences program teaches that family, in all its diverse forms, is the cornerstone of a healthy society. The mission of the program is to improve the well-being of the family through programs that educate, and to help families put research-based knowledge to work in their lives. County Extension agents within Family and Consumer Sciences do many of the same things early agents did, but their work has a much wider scope. They work across the spectrum of family needs, including nutrition, food safety, food preservation, aging, housing, community and volunteer development, health and wellness, and financial literacy education.

Family and Consumer Sciences programming in Travis County includes the following: Better Living for Texans-Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Education Program; Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program; Financial Literacy Education; Food Preservation and Safety; Parenting and Child Development; and Nutrition, Health and Wellness.

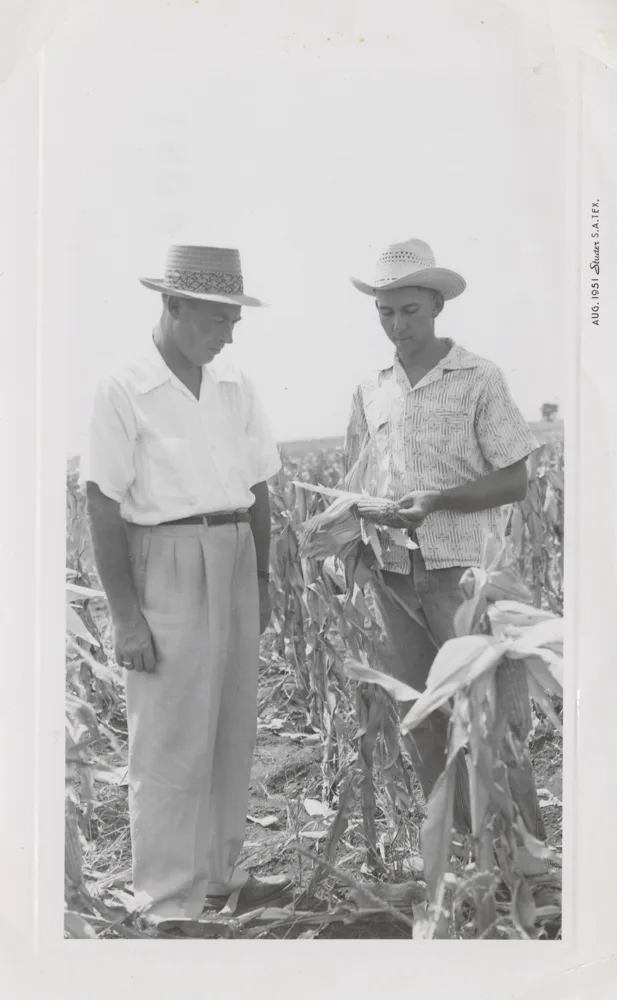

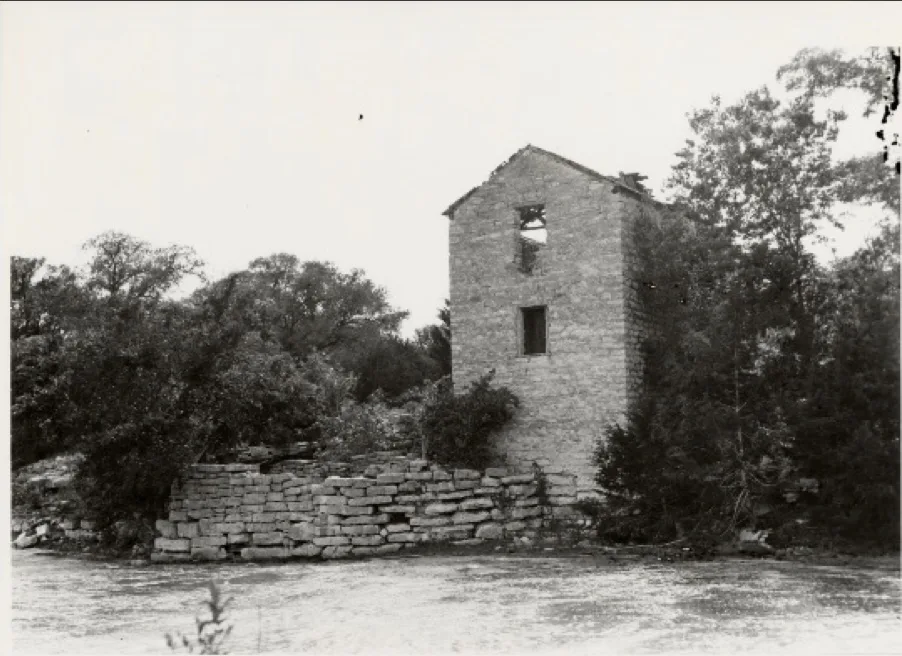

Agriculture and Natural Resources

In 1903, Seaman Knapp, a 70 year-old agent of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, established a demonstration farm in Terrell, Texas, in order to show other farmers new farming techniques and production methods. On these 70 acres, Knapp offered local farmers the opportunity to explore the benefits of scientific farming methods such as crop rotation, use of legumes, properly spaced plantings, and commercial fertilizers to increase crop production. $1,000 was collected from area farmers and businessmen to indemnify the farm against possible losses from trying Knapp’s methods; however, the money was not needed as the farm’s cotton production almost doubled.

This was the first in a series of steps that eventually led to the passage of legislation which formalized national Cooperative Extension work. In 1905, Texas A&M assumed responsibility for the expanding demonstration farm program in Texas and appointed special agents to direct demonstration farm work. This activity became the impetus for the development of formal cooperative extension farm programs, and eventually, the passage of the Smith-Lever Act by Congress in 1914.

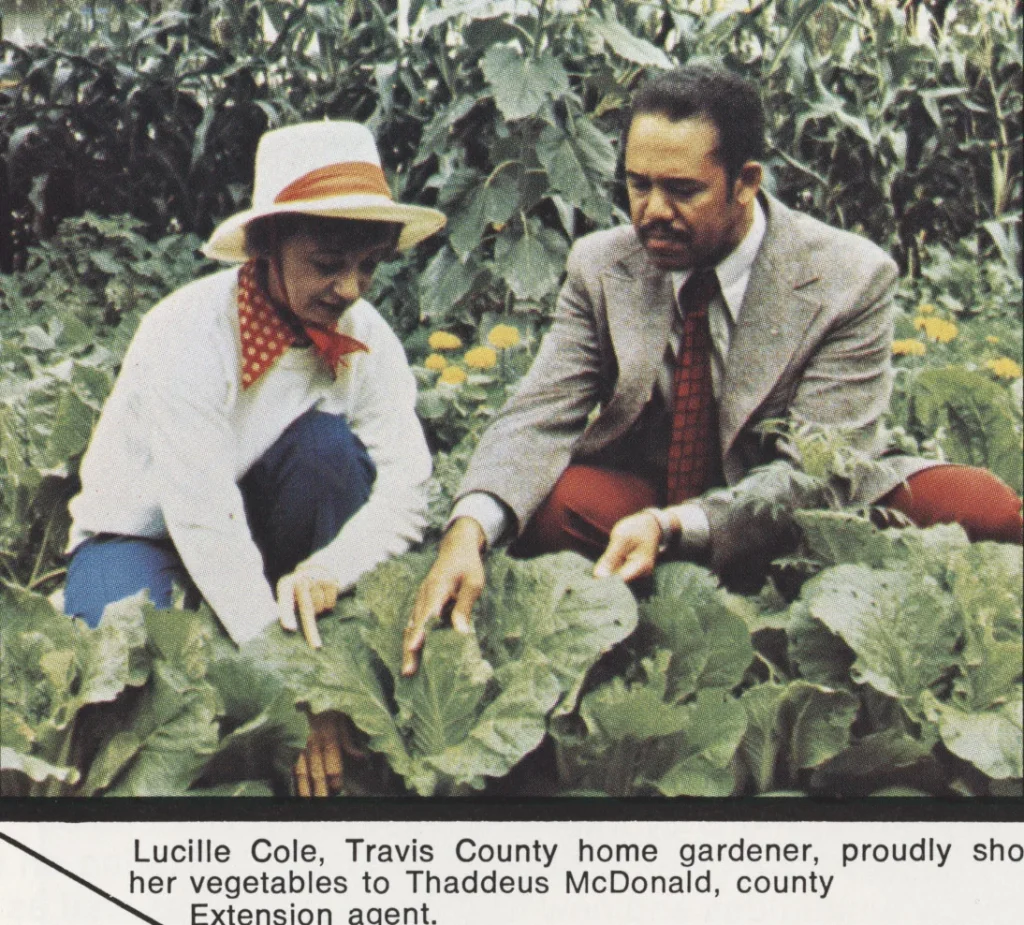

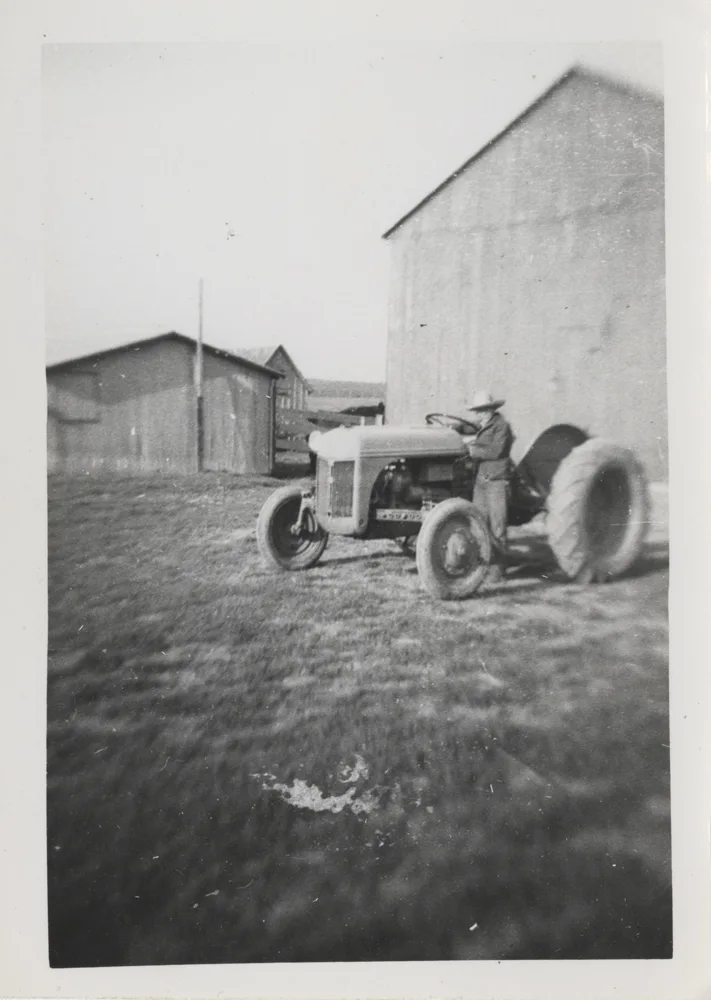

Agricultural education is a foundational concept of extension work in Texas. During the 1920s and the Great Depression, Texas county agents taught farmers throughout the state by conducting demonstrations in the areas of crop and animal production. Farm management and agricultural-economics studies were supplemented with practical demonstrations in areas such as advanced cultivation practices, livestock operations, and modern agricultural mechanizations. Model demonstration farms, such as the one founded by Seaman Knapp, were places where producers could see such practices in action.

At the turn of the 20th century, Travis County’s economy was very much dominated by agriculture. Even with the rapid increase in Austin’s population, the majority of the county’s residents lived on farms or in smaller towns. Cotton was the principal field crop in the late 1880s and remained so for more than 60 years. In 1890, 65,000 acres, nearly 30% of the county’s improved farmland, was planted in cotton; by the turn of the century the amount of land devoted to cotton had increased to 56%. However, as more marginal land was used and the soil became depleted, production levels fell. By the late 1950s, cotton accounted for only 26% of the total cropland harvested, and by 1980 it had fallen to 8%.

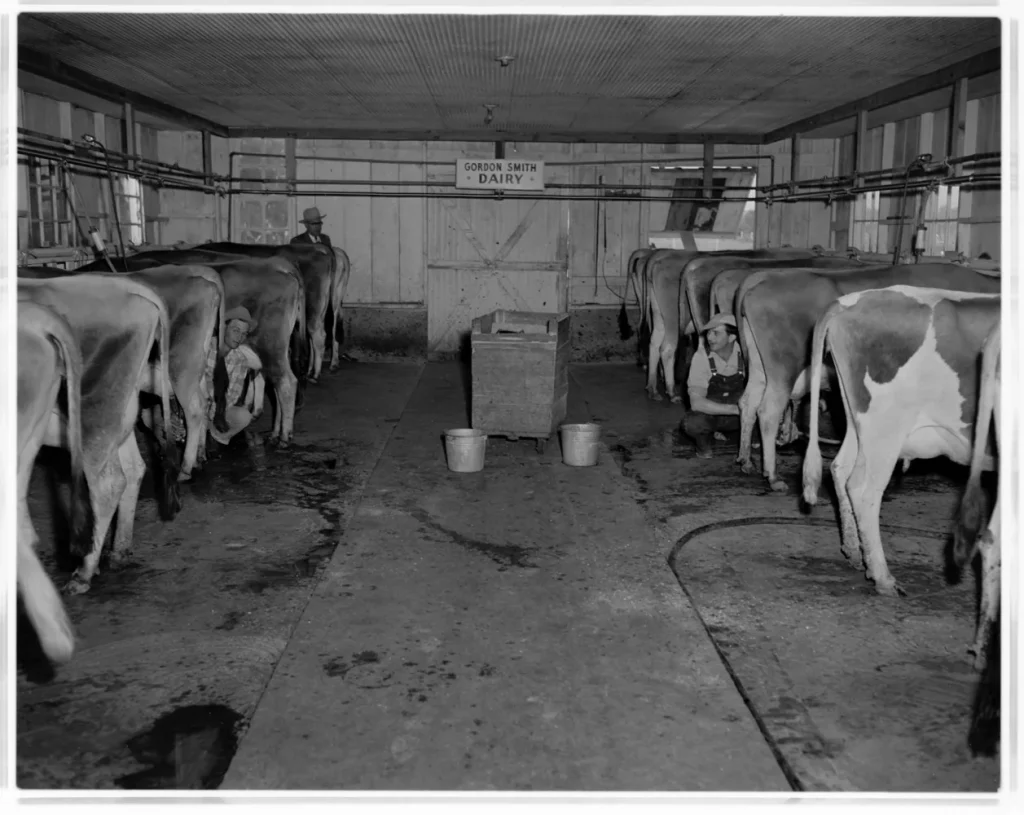

Farmers who remained in the area began to devote more of their resources to other crops and to livestock. By the early 1980s, 63% of the land in Travis County was devoted to farms and ranches. About 23% of the farmland was under cultivation, with sorghum, hay, wheat, and cotton accounting for nearly 70% of the acres harvested; other crops included potatoes, sweet potatoes, peaches, and pecans. 66% of the county’s $32 million in agricultural receipts came from livestock and livestock products, the most important ones being cattle, milk, sheep, wool, and hogs. However, although agriculture remained an important aspect of the local economy, farm receipts were greatly surpassed by the income generated by non-agricultural industries. In recent years, it was estimated only 21-30% of the land in Travis County was considered prime farmland.

Travis County’s first Extension Agent, Walter E. Davis, began his work with Travis County in 1911 as a Farm Demonstrator. Mr. Davis spent over two decades serving the county’s farmers and producers, and he was, in essence, an agricultural jack of all trades. His work spanned a wide variety of tasks, from helping residents with irrigation, to vaccinating cattle and treating sick animals, to teaching boys and girls in the various community clubs through presentations and demonstrations. As residents themselves stated in a petition to the Commissioners Court, Mr. Davis’s services as an agricultural extension agent were of untold benefit to the people of the county.

Throughout the changes in the agricultural makeup of Travis County over the years, Texas A&M extension agents have provided research-based resources and information to best assist area farmers and producers. Today, the AgriLife Extension program addresses these needs through the program known as Agriculture and Natural Resources. The Agriculture component emphasizes systems approaches that maintain and enhance agricultural profitability through the application of sound crop and animal production practices. It addresses issues associated with the social and environmental impacts of food safety and quality, surface and ground water contamination, biotechnology and natural resource management. The Natural Resources program addresses educational needs related to the management, use and sustainability of renewable and nonrenewable natural resources. Drawing on a variety of disciplines, the program focuses on such topics as soil, water, air, plant and animal life, forests, rangeland, aquatic and other ecosystems.

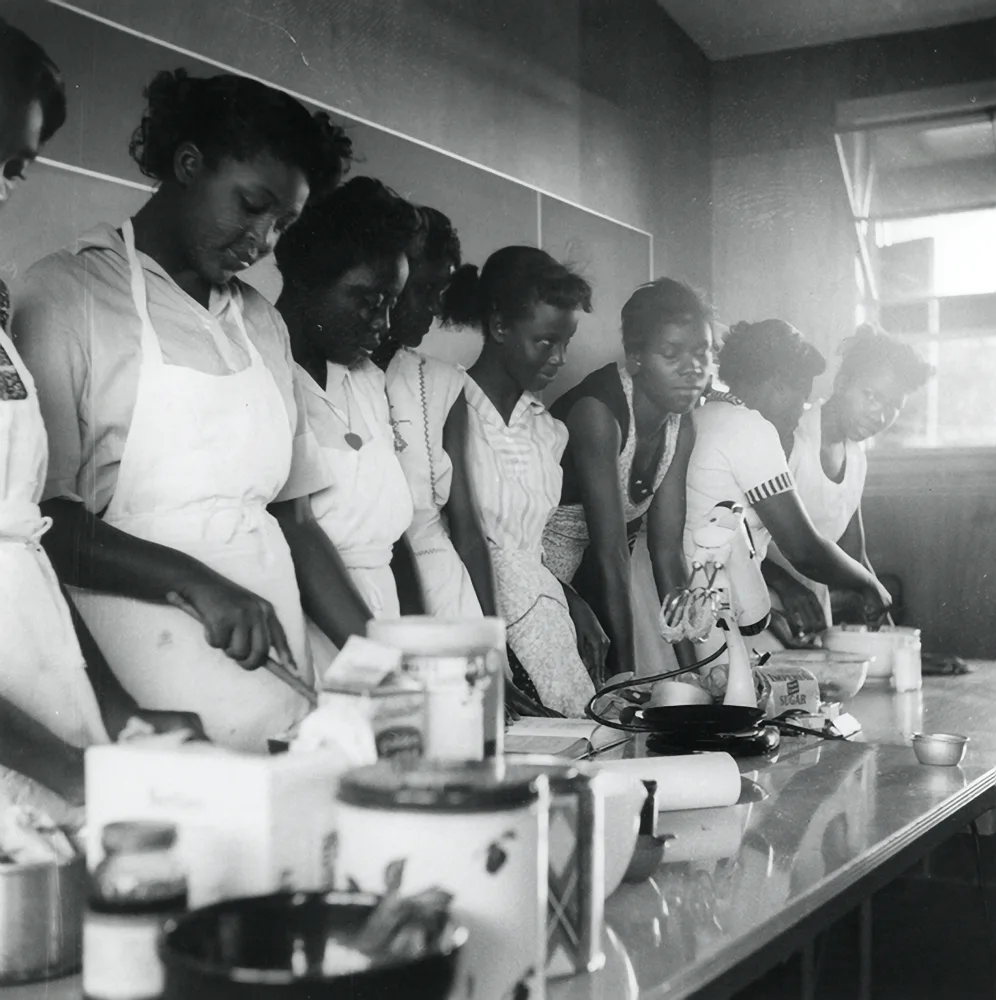

Negro Extension Work

Prairie View A&M was established in 1890 for the “colored” youth of the state, and upon the passing of the Smith-Lever Act, the work of all Negro Extension agencies was conducted through Prairie View. This arrangement was the result of the “separate but equal” practice of providing dual educational facilities for white and black people in the segregated South. The Smith-Lever Act allowed the Texas legislature to select the institution to administer the state extension services, but specified that the institution established for blacks by the 1890 act should also receive a portion of the funding. Thus, what became known as Negro Extension Work in Texas was born.

African American Robert L. Smith, a native of South Carolina and a successful businessman, teacher, and Texas legislator, was selected to head up the extension team. Programming was initially limited, focusing primarily on farm and home demonstrations. Despite limited modes of travel and communication facilities available at the time, the first year of Negro Extension Work in Texas was highly successful. In the early 1920s, funds for additional extension staff were secured, and by 1940, the service employed 46 county agricultural agents and 36 county home demonstration agents.

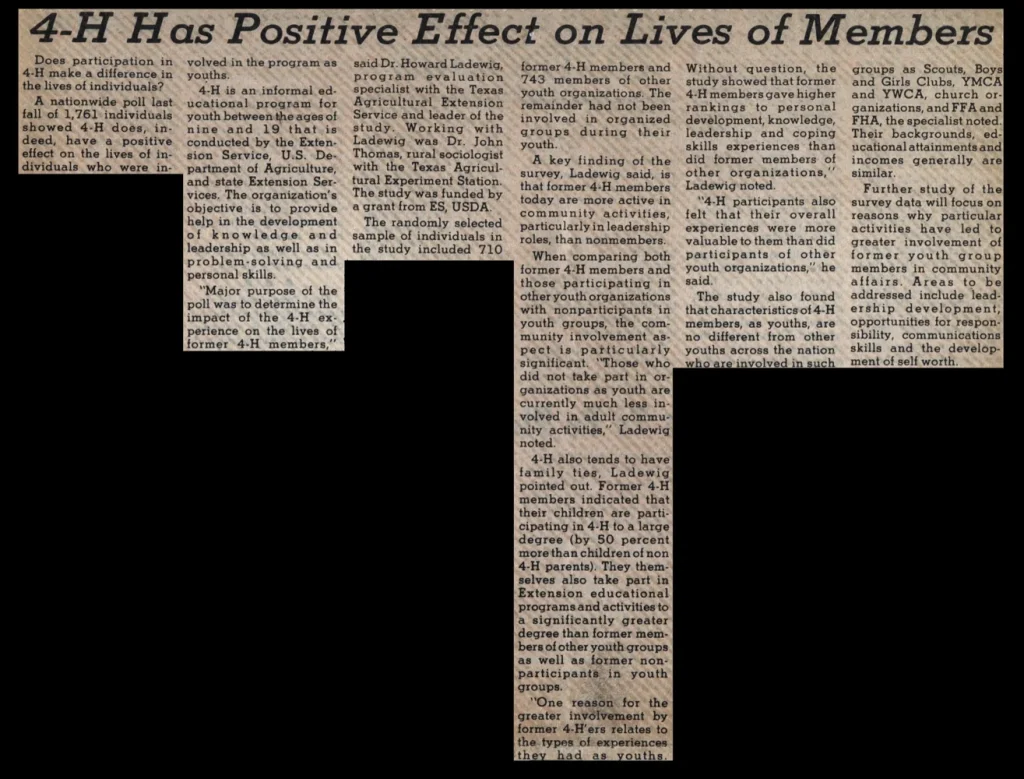

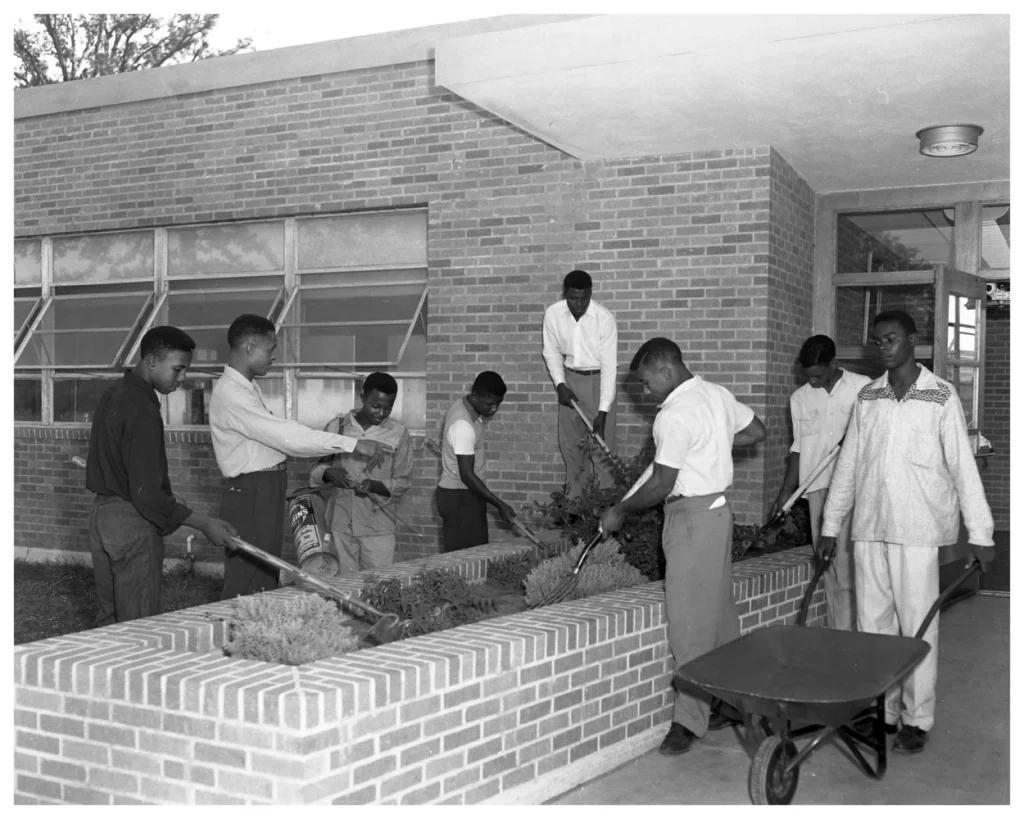

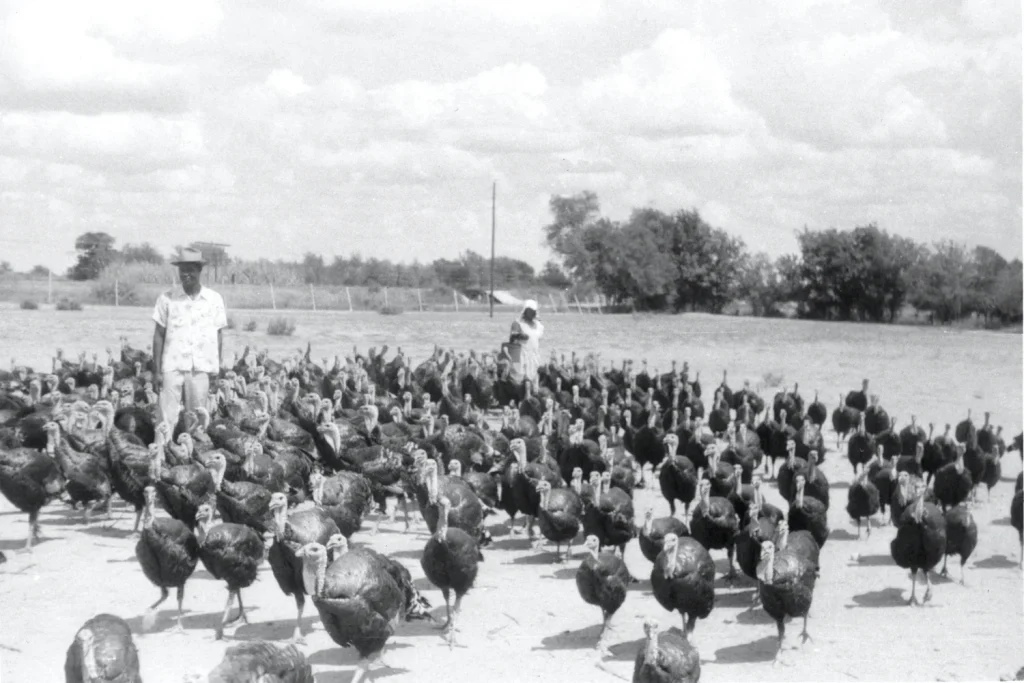

Over the years, Negro Extension Work agents assisted African American farmers and farm families with additional programs such as food preservation, housing, health, and sanitation, as well as swine, dairy products, cattle, and poultry production. During the Great Depression, the agents assisted farm families with clothing, home improvement, mattress making, and food. 4-H clubs improved life in rural areas by demonstrating to youth the latest in agricultural technology.

Travis County’s Negro Extension Work began in 1943, upon approval by the Commissioners Court for the first African American extension agent. Other counties followed suit; in the 1950s and 1960s, the Negro Extension Work staff grew to a total of 104 professional employees servicing sixty counties throughout the state. Emphasis was placed on educating leaders and community development while continuing the assistance farmers had come to expect from their local extension agents.

Thomas A. Mayes

Thomas Mayes was born in Hempstead, Texas, in 1908. A graduate from Prairie View A&M University with a Bachelor of Science in 1932, he went to work for the United States Department of Agriculture Extension Service as a county extension agent for Caldwell County. After 9 years, he transferred to Travis County, where he worked for 30 years until his retirement in 1970.

During much of his career, extension services in Travis County were segregated. Mr. Mayes’s job was to help rural black farmers and their families in Travis County. His advice and assistance were invaluable to those he helped. He is remembered for his staunch support of rural youth through the local 4-H clubs and for his practical advice in assisting local farmers. In 1985, Mr. Mayes was awarded a humanitarian award for his work in what was then the Negro Chamber of Commerce. Mr. Mayes passed away in 1997 at the age of 89.

After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the dual organization system of the Texas Agricultural Extension Service and Negro Extension Work were required to merge into one. Negro Extension Work ceased to exist on August 31, 1965. In 1977, the Agricultural Act of 1977 funded the Prairie View program separately, once again producing two cooperative extension services. Prairie View continued to oversee what was the Negro County Extension Service program but the program was modified to assist individuals with limited personal or family assets, limited opportunities or that came from communities with limited resources.

Today, Prairie View A&M University Cooperative Extension Program delivers practical research-based knowledge to small farm producers, families, aspiring entrepreneurs and youth in 35 Texas counties. It works closely with the Texas AgriLife Extension Program at Texas A&M in planning and implementing its programs.

1914 Snapshots: Life in Austin a Century Ago

Travis County today hardly resembles the small community on the edge of the frontier it once was. Established in 1840, the county’s population at the time was a mere 856 residents. This number grew rapidly in those early decades, and although the population of the city of Austin grew faster than the county as a whole, most residents lived in small communities outside the city.

By 1890, Travis County’s population had grown to approximately 36,000 residents, less than half of which lived within the city of Austin. Even though Austin’s population continued to grow, by the turn of the century the majority of the county’s residents still lived on farms or in smaller towns, and agriculture dominated the area economy.

Within the city, Austin was fast outgrowing its efforts to become a modern city. Innovations and improvements in progress at that time included a trolley system and water-generated electricity, but most of its streets remained unpaved. Outside the city, farming and ranching were king and played an essential part of the area economy. Field crops such as corn, cotton, wheat, and oats took up nearly half of the improved farmland, while livestock took up the rest.

Such rural and agricultural-based communities were in mind when Congress approved the Smith-Lever Act in 1914, a federal law that established a nationwide cooperative extension service and provided for state-based agricultural services to benefit farms and communities. That same year, global events triggered the start of a four-year conflict that eventually drew the United States into The Great War, what is now known as World War I. Extension services came to be essential on the home front, during times of war and peace, and during times of economic hardship and prosperity, educating citizens and teaching skills to improve and enhance the quality of their lives.

Even as the population within Austin surpassed the number of residents living in the county’s outlying communities, and as Travis County gradually transformed from a rural community to an urban one, extension services have played an important role in the development and betterment of Travis County and its residents. With programs such as 4-H, horticulture, agriculture and natural resources, and family and consumer sciences, residents have access to valuable information and resources that help improve their lives.