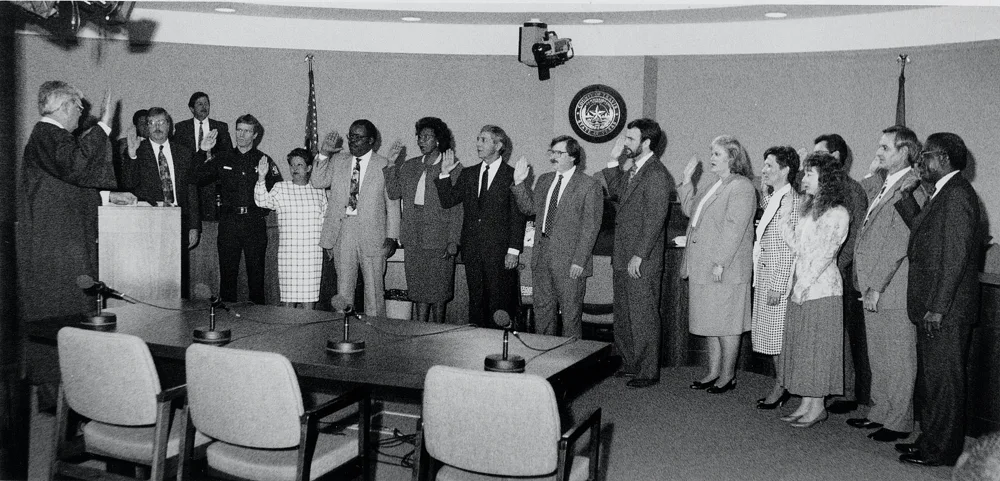

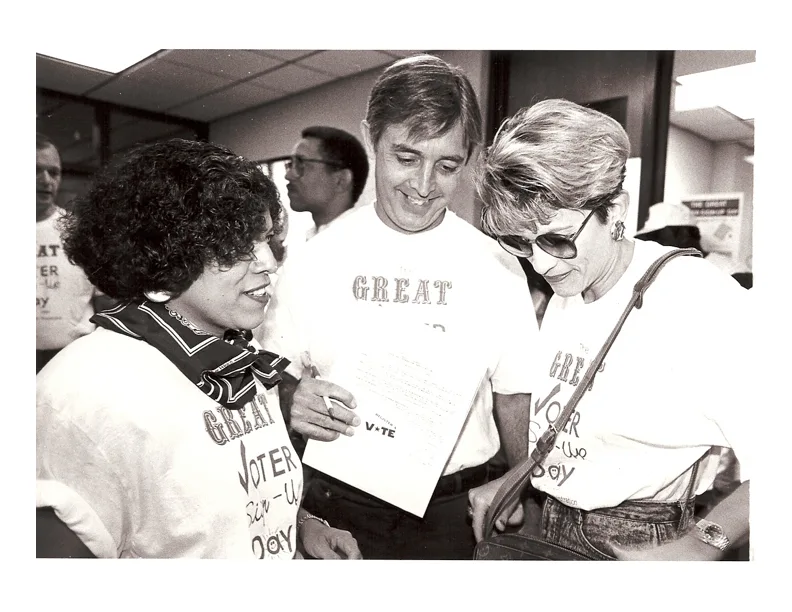

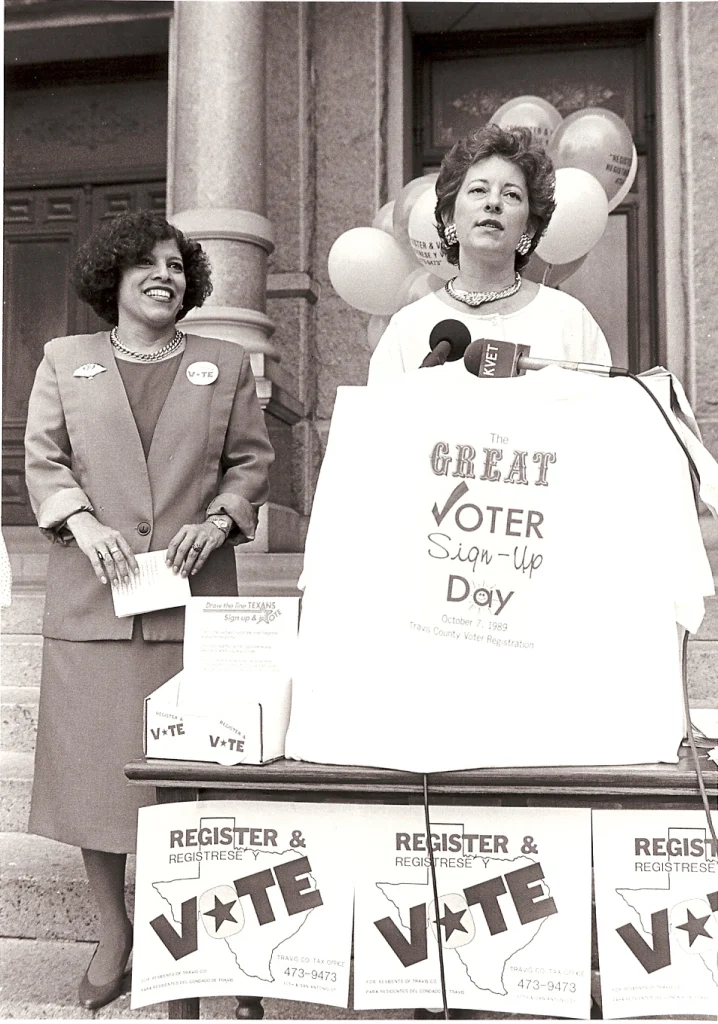

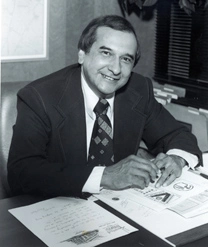

First Mexican American woman in office:

Dolores Ortega Carter, County Treasurer, 1987-present

Dolores Ortega Carter is the first Hispanic woman elected to a countywide office in Travis County. Ortega Carter is Travis County’s first female, and current, County Treasurer; she has held the position since 1987. She is also the longest serving county treasurer in Travis County history.

A graduate of Texas A&M University, Ortega Carter began her political career working for Senator Kent Caperton in his district office in College Station. During that time, she campaigned for the Senator, State Treasurer Ann Richards, and State Comptroller Bob Bullock. Her work with Bullock brought her to Austin.

Ortega Carter was elected Travis County Treasurer and began serving in 1987. As County Treasurer, she is the chief custodian of county finance and is charged with the safekeeping and investing of county funds. She works with the Legislature to pass bills improving the ways Travis (and all counties) invest public funds. The money that taxpayers entrust to county government is invested carefully, so that returns on those investments can augment county finances without increasing taxes.

Ortega Carter has served as the President of the County Treasurers Association of Texas and President of the National Association of County Treasurers and Finance Officers. She is a graduate of Leadership Austin and has served on numerous boards and commissions, including the Austin Rape Crisis Board, Samaritan Center Board, County Treasurers Association Board, National Association of Counties-Audit Committee, and various City of Austin Recreation Boards.