History Day 2008

A History of the Travis County Courthouse and Heman Marion Sweatt

On June 24, 2008, Travis County celebrated its first annual Travis County History Day. Held in the historical Heman Marion Sweatt Travis County Courthouse, the celebration featured the unveiling of an informational brochure detailing the rich history of the Travis County Courthouse and the landmark court case Sweatt v. Painter. Featured speakers and guests included County Judge Samuel T. Biscoe; members of the Page family (Page Bros. Architects designed the 1931 Travis County Courthouse); District Clerk Amalia Rodriguez-Mendoza; Judge Eric Shepperd, and Dr. David B. Gracy II, former Texas State Archivist and Governor Bill Daniel Professor in Archival Enterprise.

The Travis County Courthouse

Heman Marion Sweatt

CN02732, Craft (Juanita Jewel Shanks)

Collection, Center for American History

Heman Marion Sweatt’s fight for equality helped lay the foundation for desegregation in schools across the country. Mr. Sweatt was born in Houston, Texas in 1912. After earning a degree from Wiley College in 1934, Mr. Sweatt returned to Houston to work as a mailman. During the early 1940s, he participated in voter-registration drives in the African American community and attended National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) meetings. As the local secretary of the National Alliance of Postal Employees, Mr. Sweatt helped challenge employment discrimination in the post office, where blacks were excluded from supervisory positions.

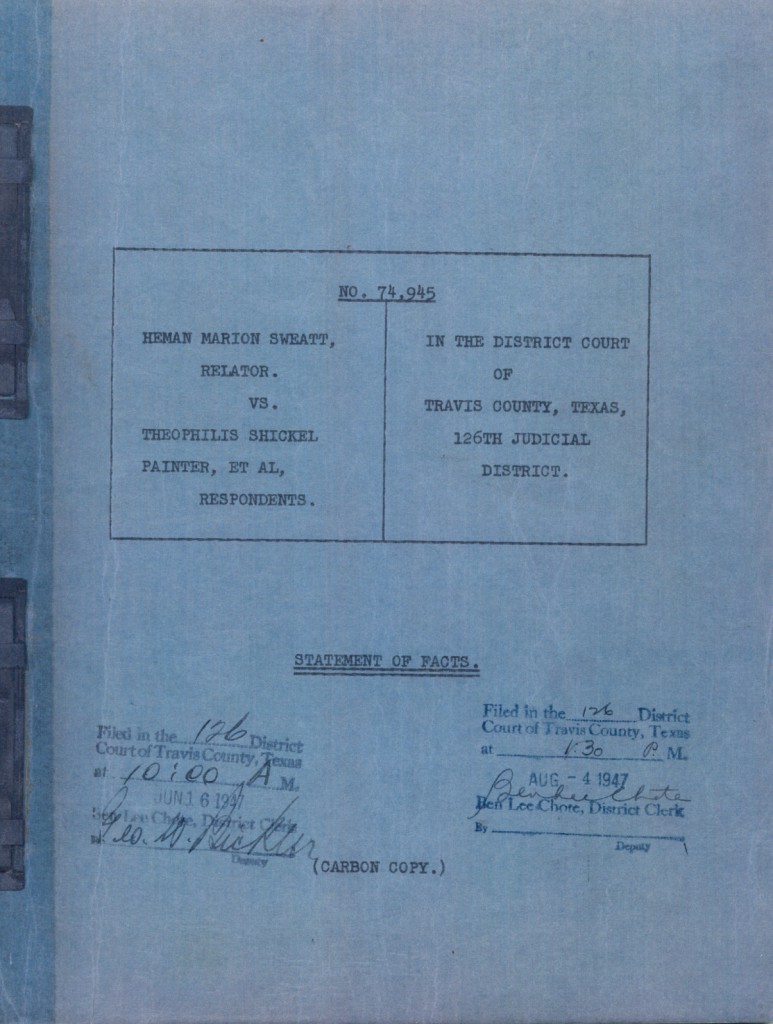

Statement of Facts, Sweatt v. Painter, #74,945

Travis County District Clerk

In 1946, Mr. Sweatt applied to the University of Texas School of Law. He was denied admission in accordance with state law, which required segregation by race. Mr. Sweatt filed a lawsuit in Travis County District Court against UT President T.S. Painter on May 16, 1946. Judge Roy C. Archer of the 126th District Court, recognizing that the State had no “separate but equal” facility for a law school, gave the State of Texas six months to “establish a law school for Negroes substantially equivalent” to the University of Texas School of Law. The State complied and a law school at the Texas State University for Negroes was established. Judge Archer concluded that the new school offered the petitioner “privileges, advantages, and opportunities for the study of law substantially equivalent at the University of Texas.”

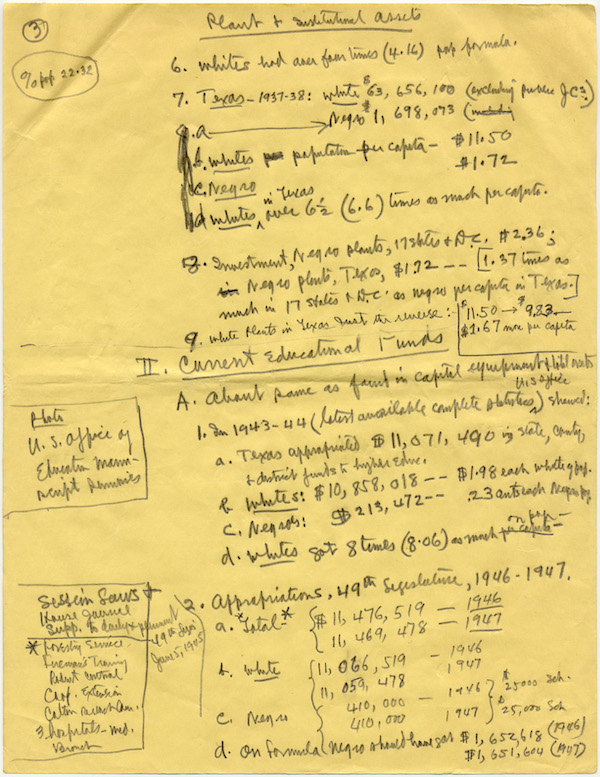

Case notes, Sweatt v. Painter, #74,945

Travis County District Clerk

Mr. Sweatt’s legal team, led by Thurgood Marshall, appealed the decision, and ultimately, in 1950, the United States Supreme Court disagreed with the lower court. While not yet denouncing “separate but equal” as the constitutional policy of the United States, the Court concluded that separate professional schools were inherently unequal. Mr. Sweatt laid the groundwork for the Court’s decision in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. In Brown, the Court finally concluded that, although the physical facilities may be equal, segregation solely on the basis of race deprives individuals of equal education opportunities. Mr. Sweatt’s case gave the Court the logic that enabled it to strike down segregation.

On September 19, 1950, following the ruling of the United States Supreme Court, Mr. Sweatt registered at the University of Texas School of Law. However, due to ailing health, in 1952 he interrupted his studies and returned to Houston. He continued to work on several campaigns to eradicate racial discrimination until his death in 1982.